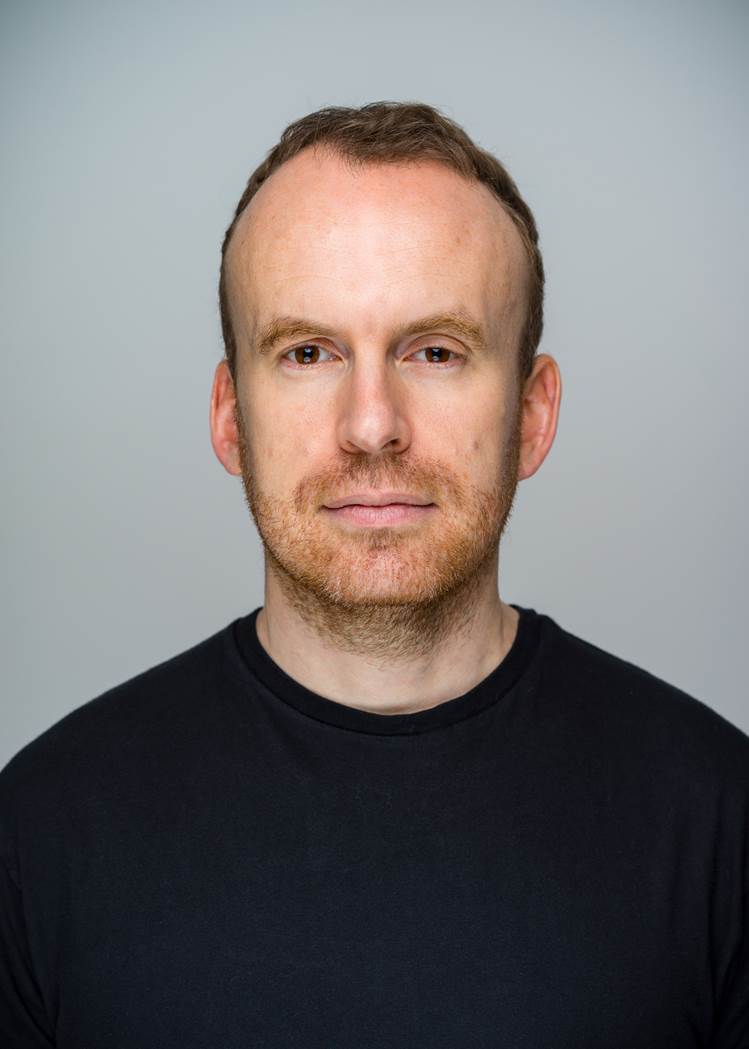

How important is it to teach young people that life isn’t always perfect and what role can fiction play in gently conveying this message? Mark Glover spoke to author Matt Haig about how the bad times in his novels are just as important as the good ones.

Back in June, author Matt Haig was interviewed for the Guardian’s Saturday Review supplement. As a fan of Matt’s work I gobbled up the profile. There was one quote in particular, about his motivation for writing for a younger audience that caught my attention.

“I want to write books that make them (his readers) happy. But to get there you have to acknowledge some darkness and death. And you can find happiness within that, then you’ve really earned happiness,” It said.

I read the quote again, and then again and highlighted the words with a pink highlighter. It was a bold statement. The words weren’t said with self-righteousness but carved from his own personal experiences of mental illness.

At the turn of the millennium Matt endured a period of crippling depression. His 2015 book Reasons to Stay Alive recounted his experience. It’s a memoir that visits the darkest of places yet is peppered with hope. If you don’t have a copy of this slim book, I suggest a visit to your local bookstore to pick one up, sit down with a cup of tea and devour it. It’s extraordinary for so many reasons.

Intertwined with stories about how close he came to suicide, or how crippling agoraphobia is, or the moment he explained to his parents why he had to come home are reasons to stay alive. Matt lists these on every other page bullet pointing things like; sunsets, love, books, films, stories and writing. All components to keep going.

Speaking on the phone from his house in Brighton, Matt explains that he was determined not to produce something that focused on the dark places that mental illness can take you. “When I wrote Reasons to Stay Alive it was directly about the worst time of my life,” he says. “Depression by its nature makes you very pessimistic giving you the bleakest outlook. However, what happens is over time, if you hang on long enough, that outlook is gradually disproved.”

He turned to writing his first novel while still in the midst of depression. He was in the North East of England, with his partner Andrea, looking after her ill mother. He had time on his hands, and with agoraphobia and anxiety gnawing away, he began to write.

The result was 2004’s The Last Family in England. It follows the slow unravelling of a family seen through the eyes of its pet dog Prince. The novel became a UK bestseller, garnered acclaim from Jeanette Winterson and was quickly optioned by Brad Pitt’s film company.

Since then he has gone on to produce ten books, writing quirky yet life affirming fiction for both adults and children. He has a knack of commenting on the fragile nature of the world that can shift, occasionally catastrophically, by the conscious or unconscious decisions that we make in life.

While it all sounds rather heavy, Matt usually filters this all through an objective narrator, such as a dog in the aforementioned Last Family in England, or in his very enjoyable novel The Humans, where its narrator (this time an alien) is sent to deal with a Cambridge maths Professor who has come close to solving an equation that could have huge ramifications on the universe.

The plot though isn’t all spaceships and lasers but more an impartial, yet revealing observation of the professor and how his family are negatively affected by the academic’s complete focus on his work and not those closest to him.

Dark threads of regret, family breakdown, adultery and even suicide run through Matt’s fiction and I read back to him his quote from the Guardian and then ask him if his own harrowing experiences of mental health issues have moulded the way he writes?

“People imagine that writing for younger people you’ve got a responsibility to shield them from things, he says. “But I think you have a responsibility to acknowledge the darkness and pain of life, and somehow find hope within that.”

So is Matt suggesting that by accepting those dark periods as part of human existence then you can begin to develop realistic outlooks and if so, how can fiction help?

“The last thing that’s going to cheer up a teenager going through change and turmoil is reading about everything being hunky-dory,” says Matt. “In fact, you can probably create a more optimistic, a more hopeful book by going to that dark place, and then finding some hope from there.”

His enthusiasm for literature and books and the power of stories is evident over the phoneline, perhaps as he saw fiction as a refuge during his illness? “It comes from my mental health problems, he says. “Fiction became a tool for me, something to escape and to retreat into that nothing else really offered in the same way.”

Born in Sheffield, Matt is from a family with a strong teaching heritage. When we spoke, his mother had just retired as a primary school head, his Aunt used to teach secondary school science and his sister, while not teaching at the moment, has taught on and off and may return to the profession.

Given this background, it’s perhaps not surprising that the central character of Matt’s most recent book How to Stop Time is a history teacher at a London comprehensive. “I think teachers play a pivotal role,” he says. “It’s one of the reasons I chose a teacher as the hero of my new novel. Everything that our society becomes is a result of how the younger generation are taught.”

Those who do teach are aware that their role encompasses more than relaying information of subject to a child. When a conversation might require someone other than a friend or a family member, a teacher is often seen as the viable third option. It’s something Matt relates to. “When I remember my great teachers as a child, I’m not simply remembering them because they fed me with knowledge about English,” he says. “I remember them as great because of a rapport or relationship that had been built up, and you felt like you were in a safe place to talk about things.”

Before becoming a writer, he studied English literature and history at Hull University, and then completed a MA in the former at Leeds University. He reads widely and when I ask what he’s currently got on his bedside table he mentions a selection of non-fiction, particularly science. Something he is interested in and might explain the fantastical angle to his stories. He lists Carl Sagan’s Cosmos: The Story of Cosmic Evolution, Science and Civilisation and Yuval Noah Harari’s Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind as influences. Fiction wise, Jeanette Winterson and Graham Greene are particular favourites.

Given his passion for reading and books, I’m keen to see what Matt thinks about the range of literature being taught on the GCSE English Literature syllabus, and in particular how modern titles, such as the recently introduced Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-time by Mark Haddon, sit alongside classics such as 1984 or Of Mice and Men and what affect this might have on students that perhaps are not too keen on reading.

“Modern books have the ability to speak to non-bookish readers as well, he says. “I think it’s very important that they see books as an art form, an entertainment form alongside films and videogames, alongside the internet, alongside music. So having some modern classics with your Orwell and Steinbeck, I think is great.”

He summarises: “The great thing about all good literature is that it has a timeless, universal quality.”

Matt recognises the challenge that teachers face when trying to bring to life for example, a dense paragraph of Chaucer, but believes passion is contagious and will rub-off on cynical classes.

“It comes down to how things are taught. You can teach the most, modern edgy novel in quite a dull way, or you can teach the most abstract 16th century text in a lively way, he says. “I think the most important thing, beyond a particular text, is that it comes down to passion, and having a teacher that can create an almost contagious passion for it.”

He recalls being taught Shakespeare as part of his A-levels, and his English teacher’s enthusiasm for a particularly challenging play, the bard’s lesser-celebrated Henry IV, Part 1. On the surface, the text seemed rather inaccessible, but the teacher’s ability to extract the life it meant that the play really struck a chord with a young Matt. “It turns out that it is the perfect story for 17-year-olds,” he enthuses. “It’s about a prince on the cusp of adulthood, and he’s got some dodgy friends, and he’s torn between two worlds, needing to face up to his responsibilities. It’s that conflict that a lot of teenagers feel.”

When I bring our conversation to a close, Matt reveals that the next evening, he’s receiving an honorary degree from Kingston University, which involves speaking to a rather large audience of graduates. He admits to feeling rather nervous. “I’m okay at book events, or interviews like this but if I’ve got to give a big lecture I struggle a little,” he says. “I’m just anticipating the heart to start going and all of those physical sensations.”

I wish him well and offer a not very useful, “Oh, I’m sure you’ll be fine.” And, given everything that’s happened to Matt, I’m sure he’ll actually be brilliant.