GRAHAM HOOPER tears himself away from exam marking to take in the retrospective at the Jerwood Gallery in Hastings.

At about this time of year I sit down in a small, dark room for around five weeks, to mark up to 300 practical art projects. I can manage about five hours before my eyes start to sting and I feel a bit dizzy. The perfect tonic, at the end of each week of relentless number crunching, is a gentle drive down to the coast to take in some sea air, eat some chips and watch the waves crashing. Hastings is further than I’d normally travel but with the Jerwood Gallery hosting a retrospective of one of Britain’s least known but most highly respected painters, Prunella Clough, I got in my car and headed off.

Hastings is situated about midway between trendy Brighton and quirky Dungeness, and the Jerwood Gallery itself is right on the seafront, with a promenade of cafés and amusement arcades behind and the busy community of commercial fishing boats and shingle shore in front. A relatively new build (it won the RIBA prize for architecture in 2013) it is a striking block of black, covered with 8000 glazed tiles, each hand-made in Kent, that echo the tall, tarred traditional net-huts that form a maze around it.

The permanent collection of 20th century British painting, featuring the work of some of our most celebrated artists on the upper floors (the likes of R.S. Lowry, Stanley Spencer and Lucien Freud) is a delight and very much sets the scene for the headline shows they offer. Their previous show, a survey of John Bradby, which brought together paintings owned by locals and national collections, was ingenious and hugely successful.

Anyone visiting Jerwood will quickly glean that it is a vigorous supporter of traditional media, if not approaches. Their annual drawing competition, with a cash prize for first place of £6,000, is held in high regard, and rightly so, as it showcases the most ambitious and courageous output each year. Clough was herself awarded the Jerwood Painting prize in 1999 (taking away £30,000 back then). That was two decades after she declined an OBE, and a CBE 10 years previous to that.

One of the reasons you may not have heard of Prunella Clough is precisely because she was so modest during her lifetime, shunning public attention in ways that might have put her more commercially ambitious male counterparts to shame. She shied away from invitations to exhibit, and before this current exhibition the last retrospective was at the Tate in London in 2007, eight years after her death.

Another reason for her lack of better profile sadly was the fact of her being a woman in an art-scene still very much dominated by men after the war, though she had other contemporaries who flew the flag for female British painting, and in the case of Gillian Ayres and Maggy Hambling continue to do so. Though the art world has necessarily moved on for the most part now, Clough’s gender is actually rarely at the forefront in her work, and rightly isn’t emphasised in this current exhibition. The source of her imagery might be considered traditionally masculine; industrial landscapes and factory workers.

Much of the work shown here has its roots in the scenes she was most familiar with in her locale. Some of her paintings feature trawlers for instance, hauling in their fresh catches, and rusty cranes rendered in muted ochre and deep sienna, typical of the post-war period in many ways. Clough once said that these subdued tones were simply a reflection of the British weather. On the day I visited Hastings I basked in beautiful sun one minute only to be running from the wind and rain the next. The climate on the coast can be somewhat unpredictable and even unforgiving, which can add drama and variety if nothing else. She seems to have enjoyed that national concern – the weather – and was also sensitive to other themes that might be considered typically British; our class system, our industrial heritage, and more generally the increasingly urbanisation of constructed environment.

Alongside her character and gender, another reason for her failure to gain the attention she deserved was a trait that could be seen as one of her strengths – her raw and playful inventiveness. What stands out immediately on seeing the cross-section of work on display is the frankly vast expanse of form and content. Her early work, figurative and vernacular in approach and subject, gives way to often radical and minimal collage and relief work, which actually appears startlingly fresh by today’s standards. Through her fifty-year career was a sound and tender response to solid and traditional visual qualities. Her intelligent use of shape, colour and line all betray her wartime work as an engineer’s draughtsman and cartographer. Much of her abstract canvases certainly suggest stylised depictions of aerial reconnaissance.

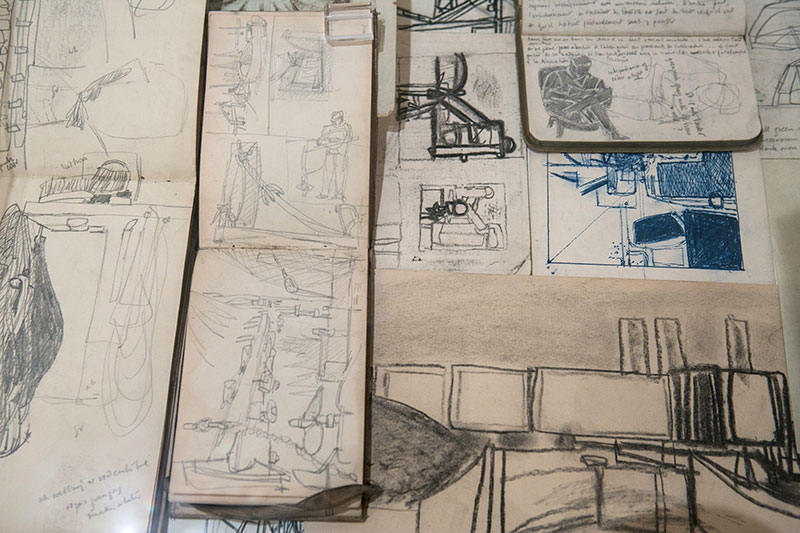

After the war Clough funded her career through teaching, holding posts at some of the countries most prestigious art schools, including the Slade and Wimbledon. She had studied at Chelsea under Henry Moore, who would no doubt have inspired an interest in the human form and a feel for the sculptural more broadly. The Prunella Clough Archive offers a fascinating glimpse into her practice as a painter. Acquired by the Tate after her death it is split into two sections; one exploring the artist’s inspiration and the other her working methods. She was evidently seduced by the everyday world around her. An accomplished photographer in her own right, the archive brings together a whole wealth of source material from close-up views of boats, abstract shadows on pavements and charming shop window displays. The texture of abandoned sail tarpaulin and stacks of colourful seaside buckets reflect an almost child-like vision. Postcards depicting desolate, dusky seascapes that have been drawn over to better emphasise the sometimes bleak and stark waterside of Suffolk and the Thames. She kept copious notebooks, each full of handwritten fountain pen annotations for colour studies. As she became drawn to the exploration of pattern she would make or find stencils that she would use and re-use; a piece of old canvas or some packaging would work equally well.

It’s strange in a way to be looking at more art in my time off. Luckily, I see no conflict between the criteria used to evaluate art in a gallery or classroom. I use identical assessment objectives daily to judge the work of my students as I do the work of the established canon. I’m pleased to be able to say that and share that belief with my students in one of my first lessons each September. I think the exam board has been sensitive, respectful and considered in identifying what it is that constitutes sound and distinguished artwork. It needs to be as objective as possible of course, but also reflect the natural methods and approaches that might be said to comprise the artistic sensibility.

If I were marking Clough’s work, I think she’d score very highly for her experimental use of materials. The exploratory nature of her technique and process is clearly and confidently demonstrated, and as with many accomplished artists, the ability to reflect on and refine their work is equally intuitive. Her ability to record – in words and pictures – her ideas, observations and insights along the way is also evident and highly developed. She presents her responses in ways that are meaningful, personal and intentional; another key criteria when awarding marks.

But where she might fall down is in her development. Though an exhibition of the size presented in Hastings, certainly in proportion to the time-scale it must cover, can at best only ever be relatively brisk, its weakness lies in its lack of sustained coherence at times. Whilst development is to be encouraged and celebrated, one feels that though the work ethic is sustained, the focus jumps somewhat. Within a room we see divergent uses of media (oil paint right through to scouring pads) that reflect a degree of incongruence. That is most probably a result of the selection and arrangement rather than of Clough’s practical creative progression. If I wished for anything it was that the work be presented in a way that sought out and reflected the ongoing underlying conceptual and visual links, so as to create a better sense of continuity where there is otherwise a tendency to suspect fickleness or superficiality. I would want to evidence what connects her early use of colour with her that in her later paintings. Indeed, giving each room a clear focus rather than a chronological format might have been better suited to displaying this particular body of work. Action, detail and space as focal points would all have provided a rewarding and insightful lead in.

Enjoying the café menu on leaving Jerwood, the world was transformed into a Clough painting; the patterned tablecloth, the arrangement of the salt and vinegar, the view of the boats outside. Good art does that; like fishermen pulling in a net only to discover a mermaid.

www.jerwoodgallery.org/whatson/40/unknown-countries

www.tate.org.uk/whats-on/tate-britain/exhibition/prunella-clough