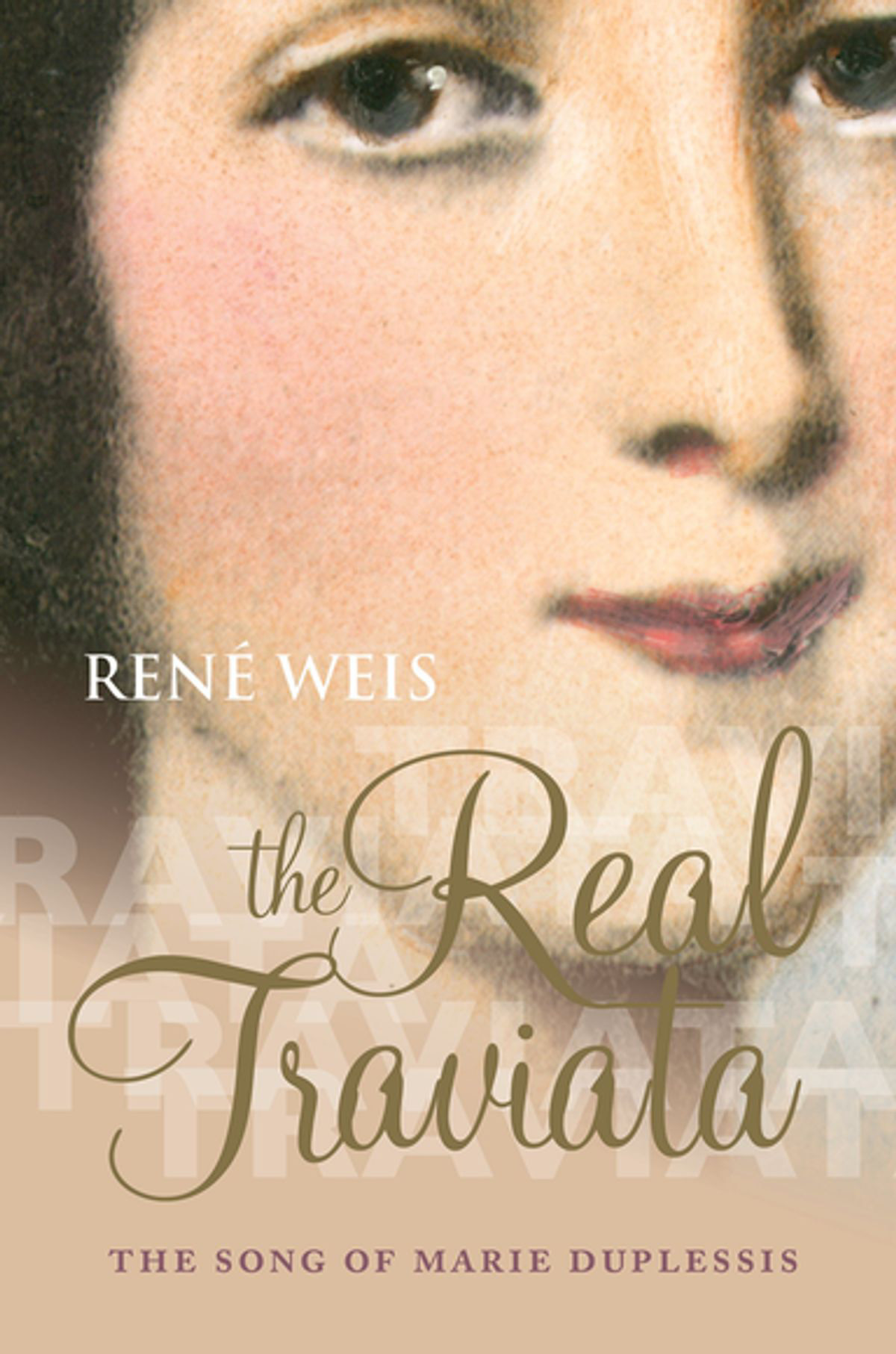

By René Weis

Published by Oxford University Press

Verdi’s 1853 opera La Traviata is based on La Dame aux Camelias, an 1848 novel by Alexandre Dumas which he reworked as a play in 1852. The inspiration for all of this was a French courtesan, named Marie Duplessis who shot from poverty to luxury and refinement before dying of tuberculosis in 1847 at age 22. Dumas was one of her many lovers. Verdi wasn’t.

René Weis’s immensely detailed biography of Duplessis presents a woman who endured an appalling, impoverished childhood, more or less abandoned by a desperate mother, sexually abused and later effectively pimped by a paedophile father and at one point reduced to begging in order to eat. No wonder she grabbed the chance to use her assets to better herself when the chance came her way. Still in her teens – the path was a complex one, scrupulously researched by Weis – she was “protected” by a series of wealthy, influential, well connected men each of whom understood that he didn’t have exclusive rights to her time, charms, elegance and body.

Duplessis became, in a very short time, a cultured woman, knowledgeable about art and literature and able to play the piano. Listz was one of her lovers. So was his friend the rich and flamboyant music-loving Felix, Furst von Lichnowsky along with Conte Olympe Aguado, son of the banker Alejandro Aguado who at his death left his three sons his art collection and an estimated 60 million francs.

According to this impeccably researched (arguably too packed with expendable minutiae in places) biography, Duplessis was also a vulnerable, sensitive woman who suffered a lot when others treated her badly as well as during the illness which preceded her tragically early death.

With its rippling melodiousness, dramatic depth and simple plot La Traviata is one of the most popular operas of all time. It is therefore interesting to read such an entertaining and informative account of its genesis. And it speaks volumes for Duplessis’s charisma that she was adored by and able to influence so many people and that we are still intrigued by her 170 years later.

Review by Susan Elkin