Throwing away a script and using real words from real people from real events can seem daunting; yet verbatim theatre can engage students in ways that traditional forms cannot. Directors, playwrights and theatre companies are offering a genre that uses honesty, truth and authenticity as its foundations. Mark Glover finds out more.

Robin Belfield’s first experience of verbatim theatre was a personal one. His father, a British missionary posted to the Bahamas, kept diaries of his time there; anecdotes of an Englishman on a remote Caribbean island. Robin inherited a text rich in colour and life, bursting with vibrant stories and experiences; a text primed for verbatim adaptation.

“I was able to take his first-hand accounts and his verbatim experiences; his thoughts and feelings and I turned it into a piece of theatre,” says the writer, director and producer, recalling his time spent adapting his father’s words. “You can’t just put his diary on the stage you have to edit it, shape it and turn it into something that works for the medium I was presenting it in.”

Verbatim theatre, for those not fully aware, are plays constructed from the precise words spoken by people having been interviewed about a particular event or topic. David Hare documented the 2008 financial crisis in The Power of Yes, and Alecky Blythe’s musical London Road is set around the 2006 Ipswich serial murders.

Despite this technical simplicity, the genre straddles a large spectrum and Blythe’s own verbatim theatre company, Recorded Delivery, is perhaps at one end. Actors, instead of learning a text, are fed words through an ear piece to deliver. It is, according to Robin, the purest way of respecting what the genre means. “If verbatim is as closest we can get to the real thing then that [Blake’s technique] is. It means you’re not even allowing for an actors’ ego or nerves or choices they are literally repeating.”

Robin, author of Telling the Truth: How to make Verbatim Theatre (reviewed in April’s issue of Ink Pellet) directed a play at the other end of the form’s scale called Walking the Chains, a blend of verbatim text and fictional input. Set in Bristol and centred on the city’s Clifton suspension bridge, the play blends modern-day verbatim dialogue taken from the structure’s maintenance teams, and historical verbatim text from Brunel’s time constructing it while also fusing fictional elements. “In the field of verbatim theatre there is so much scope for choice and artistry and creative freedom, as long as,” Robin affirms, “the use of those words has integrity and retains an authenticity of the original voice.”

Having worked on Hare’s The Power of Yes as a Staff Director at The National Theatre, Robin witnessed the authentic and effective preservation of voices enveloped in a very heavy subject. “He was able to shape dense, technical and political verbatim text and I watched how he, the actors and director Angus Jackson brought that to life,” Robin recalls. “It made the text immediate, real and dramatic for the audience.”

One company utilising the form across school audiences is The Paper Birds Theatre Company. Established in 2003, the company didn’t begin verbatim theatre until five years later. Even then, it took a newspaper review to inform them they were. “Someone who reviewed one of our shows referred to us as verbatim and we actually had to look it up!” laughs Paper Birds’ Co-Director Jemma McDonnell. “I’m sure there were other verbatim companies, but we didn’t really know about it and as soon as we looked it up we realised we had been,” she smiles.

The company produce a range of verbatim theatre among their output and ensure integrity and authenticity are at the heart of this work. The form has no script, as such, with material usually gathered through interviews or video recordings; the nature of which can often be quite sensitive. London Road for example, used comment from prostitutes who worked in Ipswich, as well as residents and journalists who covered the story, it requires therefore a tactful approach; something Jemma and her company embrace fully. “This isn’t a game, this isn’t fiction, this is real life,” she says earnestly. “It’s very important that you take it seriously and we definitely do. I don’t think we would ever go forward with a production if everyone wasn’t happy with what was in there and people are represented. We set ourselves a series of guidelines of what we’re comfortable with and not comfortable with. How are we using this material? How are we editing it and how are we portraying people?”

In fact, the role of playwrights in verbatim theatre is probably closer to an editor than a traditional writer. Indeed, Katherine Viner, playwright and Editor-in-Chief at The Guardian skilfully weaved the verbatim play My Name is Rachel Corrie, collating and selecting diary entries and emails of Corrie, an activist who was killed in Israel while trying to protect a pharmacist’s home on the Gaza Strip. Reviewing, Michael Billington said: “Theatre has no obligation to give a complete picture. Its only duty is to be honest. What you get here is a stunning account one woman’s passionate response to a particular situation.”

Robin shares Billington’s outlook: “Theatre is always about truth,” he says. “I think theatre practitioners are always trying to get to some element of truth be it abstract, emotional or a realistic truth. Verbatim theatre is the technique that enables the theatre practitioner to get closest to the truth as possible.”

Introducing the form to the classroom, can, on the surface, seem like a challenge. As mentioned, there is no traditional script and the approach could seem rather restrictive to students used to reading lines. Jemma, however, thinks the genre offers a personal connection with young people that devised pieces cannot. “If students are given a devised piece about a humanitarian crisis, it can be something that feels very different and alien to them,” she explains. “As soon as you start to bring in verbatim and say to them ‘this is a story about a survivor and this actually happened,’ straight away they’ll become much more interested because it starts to feel more 3D to them.”

“If we want to talk about the immigration crisis and the concept of home, we could ask the students to speak to their parents and talk about what home means to them. The students come back in the next day with this incredibly rich material and they start to see how interesting and exciting it can be. It makes it really relevant to them, to their worlds and their lives. It’s important to engage students in that way.”

Robin seconds the outlook: “I think it’s a brilliant technique for teachers and students because it’s another way of devising. If you don’t have a play script you can make your own. If I take words that already exist, a story that exists then it is a way of telling a story, which is ultimately what we’re all in the business of doing.”

The Paper Birds are soon to tour schools with Thirsty, a play about binge drinking, where the scenery is graffiti scrawled toilet cubicles and the actors convey stories of alcohol abuse, sent in anonymously to the company. Jemma says it’s a powerful work that will resonate with the audience. “I think they [young people] will like it because there’s an honesty there. We’re not trying to protect them from these stories, they’re not stories to warn them, they’re real stories coming through and they respect it and actually listen to what’s being said.”

The genre offers teachers a different approach to student engagement. There’s an argument verbatim theatre can be just as, if not more fertile for class involvement than a traditional devised approach. Truth, authenticity and honesty are important parts of being human. Studying verbatim theatre can only enhance these traits and that is no bad thing.

Robin Belfield’s book Telling the Truth: How to make Verbatim Theatre costs £12.99, published by Nick Hern Books www.nickhernbooks.co.uk

Thirsty by The Paper Birds Theatre Company tours from October. You can find out more information at www.thepaperbirds.com

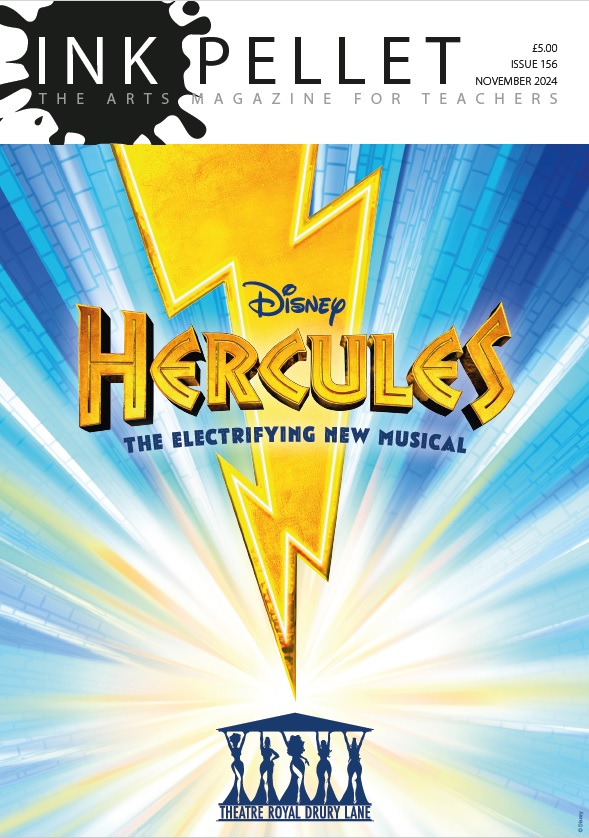

IMAGE ABOVE: Thirsty ©Paperbirds