There’s art out there, just waiting for you, ready to inspire your pupils and instigate cross-curricular learning. Graham Hooper discoveres a treasure trove of resources – both old and new – and hopes you will take up this fabulous opportunity.

Stored in a freight container on the edge of a farmer’s field, somewhere near Didcot, is what remains of the ambitious School Prints loan service; art from around the world and spanning many centuries, quality prints mounted and framed, ready for schools to hang in corridors and classrooms. Up until the mid-1990’s these were circulated, a term at a time, to schools up and down the country for a nominal fee, always with the aim of getting young people engaged by and engaging with art history.

In boxes filling shelves four high and forty feet long, literally hundreds of thousands of postcards, collected from major galleries and museums across the globe, are also now in cold storage, waiting for a new life, in classrooms and studios. In packs arranged by theme (from trees to windows) or movement (surrealism to expressionism) and genre (sculpture, textiles, posters) these were sold, still are sold, to teachers grateful for tactile, convenient and charming resources to get students thinking, exploring and ultimately painting.

All this has its roots in School Prints Ltd., set up after the war by Brenda Rawnsley, who was determined to promote art education, believing it to be humanising, as indeed it is, deeply. She had the energy and audacity to commission leading artists of the day to provide images that could go out to any and every establishment to get children looking at art and their immediate surroundings in new ways. For many of these school pupils, in an age before Google images, let alone significant public collections dotted around the country, it was the next best thing to a trip to the Tate (not Tate Britain as it is now). If you lived outside of London this was the only chance to really experience the work of Henry Moore or Paul Nash.

The story goes that she even took out a £10,000 bank loan, chartered a plane to France, to persuade Picasso to join in, and he did! Suffice to say the original project was a huge success although a second series by these major European, and much less figurative artists, was a little too avant-garde for schools, and the plan came to a halt eventually.

But the Hepworth-Wakefield Gallery in Yorkshire have recently re-commissioned some our most popular and enlightened artists to produce a new set of images, using the original brief, and the results are now on show. The images have been created alongside schools and the prints can be bought relatively cheaply. They are as varied and thought provoking as the people who have made them, the likes of Turner Prize winners, Grayson Perry and Helen Marten.

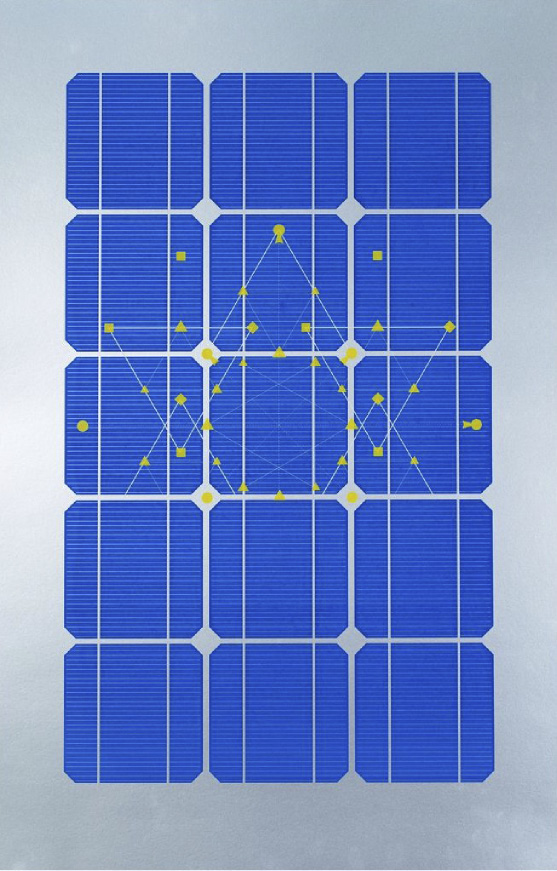

Haroon Mirza’s print is the result of thought and investigation into physics, specifically fundamental particles and energy. Colour and grid-forms are used in a highly geometric composition that brings the beauty hidden deep in nature to the fore. The associations – star constellations, mapping, religious iconography – are all present, in a work that can promote discussion, creative writing and in particular cross-curricular study.

Of the six images available Martin Creed’s is the most accessible, perhaps almost too child-like. It consists of six broccoli prints (not potato slices in this instance, broccoli instead being his vegetable of choice) that have been block printed in different colours. The idea that ‘a child could do that’ is probably the whole point. Non-art specialists in primary schools can take fruit and vegetables, most or least liked, slice them, and using no more than powder paint and glue mixed, replicate the work of the famous artist. The similarity and differences between different varieties becomes apparent quickly. Discussions about healthy eating are instigated. Colour mixing is better understood. Pattern and arrangement are explored. All this for a mere fifty quid plus postage, and that’s for the full set of six by each artist represented.

Creed’s simple if evocative vegetable prints provide a useful link to the work of another artist, Karl Blossfeldt, who was also inspired by natural forms. They are already on show up and down the country. Quite recently a display of the close-up flora studies by early-twentieth century German Photographer Karl Blossfledt were shown near me. I could take students easily, or encourage them to go off their own backs.

His training as a sculptor in Pre-War Germany is clearly evident in these often-microscopic views of plants. Stamen, spikes, prongs and petals are only just obvious to the naked eye at thirty times their normal size. Hailed as revolutionary in their day, they were indeed eye opening, for science and the general public, who had never before been able to see these everyday phenomena at such range.

In soft greys they might resemble William Morris wallpaper designs. For an amateur botanist, most concerned with objective recording of natural forms, they are remarkably pleasing aesthetically. To see a room filled with these specimens is a genuine launch pad for student creativity. Whilst Blossfeldt made his own camera (something pupils may indeed wish to attempt) most smartphones have the technology to get up close to flowers in their garden or pot plants around the school, and record the shapes and patterns. For young people to understand that beauty exists in the most mundane or otherwise unassuming places is often a revelation. I have seen it myself. In fact much of my working day is spent convincing teenagers that our job is not to so much to make beauty look beautiful, but rather to discover what we thought unappealing, unworthy of our attention and joy, and recognise its inherent interest and value. A complete set of Blossfeldt’s lithographs is available to any venue meeting the criteria through another scheme open to schools and colleges at modest cost.

For many students the opening of new galleries since the war, across the country, outside of the capital has done a great deal to reach out to new audiences, young audiences especially, so that they can see art first-hand. Major venues are thriving, with inventive and exciting exhibition programmes and educational schemes to match. For schools and colleges near one of these galleries, or with good transport links, and teachers willing and able to organise study visits, experiencing good art can be not just motivating but powerfully transformative.

The Hayward Gallery in London has had for some time now a whole set of touring shows for hire. Again for centres with the space to exhibit work, collections of pictures by artists as diverse as the American documentary photographer Walker Evans through to Cornelia Parker can be had, complete with publicity material and wall captions.

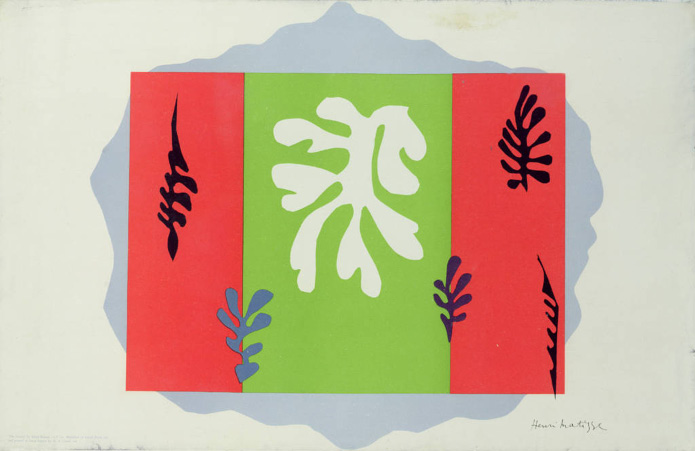

Another useful starting point is the series of colourful cut-outs of Henri Matisse. The same work was only recently displayed at Tate Modern in sell-out shows, and is another set available for loan in your school. These are often figures, seated or kneeling, and rendered in rich, deep blue paper collage. With limited mobility towards the end of his life Matisse took to using this method of working as he could achieve the decorative effects he loved so much yet still explore through careful observation depictions of light and shape. These works can be seen this year in Durham, Bridport and Ayr. Go see. Take the kids. Then on returning home stop off to buy some big sheets of brightly coloured paper, and using household scissors, make your own. That’s the idea here.

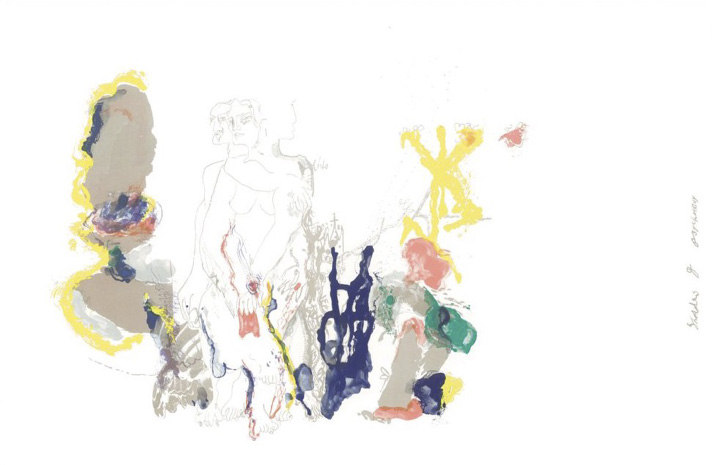

Here’s another interesting pairing. Helen Marten’s Hepworth-Wakefield image continues the theme of the body with a group of figures, huddled, moving, drawn in transition. Who are they? Friends perhaps, chatting in the playground, or a family group, in celebratory embrace. Are the colours symbolic? The lines are delicate and the forms fragile. The selfies of the French photographer Claude Cahun, dating back to post-war Jersey, see her adopt a range of theatrical personas, as a way of scrutinising genre and identity. They show the body, almost in dance, as a series of postures or stances, employing masks or costume. It’s a perfect way in for a dance or drama department to work with the art teachers to devise original work, to collaborate on a joint venture then lets students really think about who they are, how they see themselves, who they would like to be and how others might see them.

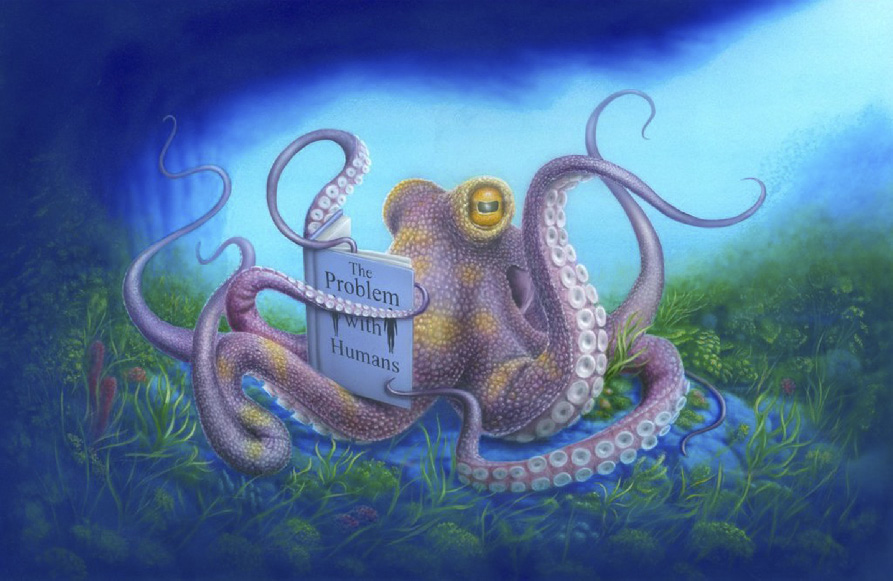

I want to mention lastly Jeremy Deller’s print. In what looks like a book illustration, an octopus, sitting in his undersea garden, is reading a book of all things, one entitled “The Problem with Humans”. We are familiar with The Beatles tune Octopus’s Garden. Is there anyone who doesn’t know most of the words by heart? So what is the problem with humans? That is the question. That they pollute the sea? That they don’t read books anymore? That seafood has become an endangered delicacy rather than a staple of global diets? Play the song. Illustrate the book. Write the essay. Do all three!

There has never been a better time to get out to see art, or get great art in to see you.