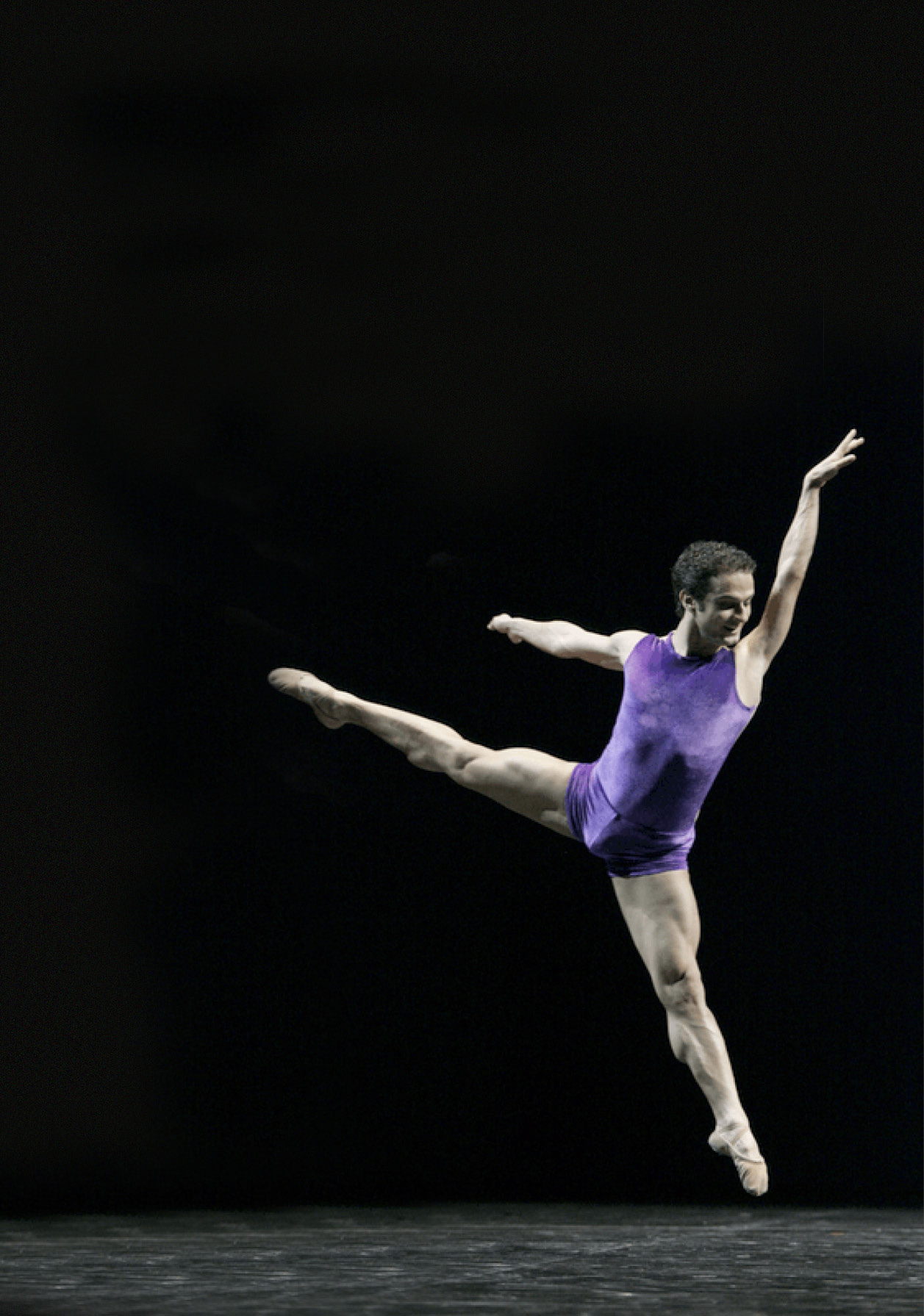

In this, the first of a regular feature examining issues facing the arts, Susan Elkin posses the question why so few men still take up ballet

Earlier this year I caught My First Cinderella at Orchard Theatre Dartford during its tour. This is an English National Ballet initiative to introduce pre-schoolers and upwards to the joy of ballet – and it’s a double bonus because also it’s a wonderful quasi work experience job for the young English National Ballet students who perform these “baby” ballets each year. The first tour was in 2012 since when over 200,000 people have seen an ENB “My First” production.

They’re popular and Orchard Theatre was heaving with little girls in pink frothy frocks, mothers, grandmothers and aunties. But where were the young boys and their fathers, grandfathers and uncles? Doing something else, clearly, because very few of them where at My First Cinderella. Overall I reckon about one person in ten in that audience was male.

And I remember leaving Peacock Theatre in London following an earlier My First Ballet behind a mother, father, girl and boy. “Well did you enjoy that?” the father asked his son. And then, before the boy, 7 maybe, could draw breath to answer. “No it wasn’t much for boys, was it?” said the father.

In short, even in 2017, ballet has a “girly” – even effeminate – image and parents go on perpetuating the stereotype either by not taking their boys to see it or by telling them they won’t enjoy it if they do. And yet there’s nothing remotely namby-pamby about adult male dancers. They are extremely strong. “Never pick a fight with a ballet dancer” I was once advised by the principal of a major dance school. Some football clubs send their trainees to ballet classes for strength, balance and co-ordination training. In some ways ballet is simply an artistic, musical form of athletics and no one ever sneered at that for being just for girls and wimps.

Billy Elliot – the story of a working-class boy who overcame the prejudice of his macho miner father and brother to train professionally and eventually star in the Royal Ballet – dented some of the negative feelings about boys and ballet. First the 2000 film, and then the musical which ran in London for 11 years and toured the UK and Ireland earlier this year, were seen by millions and helped to change attitudes. Suddenly boys were coming forward and signing up for classes more freely. And dozens of boys had to be found, auditioned and cast to play Billy during that long London run. Boys were interested. Hurrah. In the industry, they called it “the Billy effect”.

But is enough being done to encourage boys to start dance in general and ballet in particular – or to keep the Billy effect going? Barry Drummond, First Dancer with English National Ballet, whom we interview on p.30 of this issue of Ink Pellet, thinks there will always be more that the industry can do. I still visit performing arts schools running dance classes – both part-time ones for children and vocational establishments for young adults in which a tiny handful of boys are like gold dust.

What is it that puts men off? Well I know several perfectly decent, kindly arts-loving men who tell me quite seriously that watching men in tights makes them feel uncomfortable. Of course that’s partly ignorance and partly lack of a fully rounded arts education. It is also something to do with sexuality. Some men seem to think, even subliminally, that enjoying near naked men moving in interesting ways is some sort of affront to their heterosexuality. And that’s borne out by the fact that none of the gay men I know seem to feel this way.

I also suspect that this may be a British problem. Many of the dancers in our big ballet companies come from elsewhere in the world where, it seems, that it’s as “normal” for a young male to take up ballet as it is to take up, say playing the French Horn or training as a singer.

Well somehow, if we want ballet to have a secure, lasting future – with a reasonable number of home grown male dancers – then we have to set up lots of projects, and support them, to encourage boys as many companies with education departments are doing.

But we also need to find ways of changing public attitudes and that’s much harder. In The Billy Elliot story, Mr Elliot eventually softens and is very proud of Billy’s achievements. That is still not, unfortunately, a likely outcome in far too many families.