From playing village halls to touring Los Angeles, Kneehigh has come a long way since it began as a schools’ theatre company in the early 80s, yet its Cornish origins run deep and continue to influence its productions. Mark Glover finds out more about this extraordinary touring company.

Thirty-seven years ago, a primary school teacher working in the South Coast of Cornwall gathered a together a group of friends including a supermarket sign-writer, an ex-dancer and a thrash guitar player and set-up the theatre Company. That teacher with a quirky passion for theatre was Mike Shepherd and the company was called Kneehigh.

Born in Cornwall, Shepherd headed to London, pursuing acting opportunities that never quite materialised. He returned to the South West in 1980 and began touring schools with his new outfit, it was here the name Kneehigh from the saying ‘knee high to a grasshopper’ was taken; a nod to the small children they were playing to.

Mike and Kneehigh soon graduated to playing the South West’s strong village-hall circuit performing small-scale shows in rural communities. As ideas flourished the company would out-grow these smaller set-ups; its creative heart, however, would continue to beat from these rural pockets.

A natural progression to mid-sized venues should have followed, however given Cornwall was some years away from a venue of those capacities (The 969-seater Hall for Cornwall re-opened in 1997 with 969 seats) Kneehigh went, quite literally, back to its routes.

Mike began working with the late Bill Mitchell, who would later start Wildworks, putting on shows in the woods, fields and quarries of Cornwall, essentially inventing large-scale outdoor theatre work. Throughout the 90s Kneehigh became renowned for this type of natural theatre.

Then in 2000, Emma Rice joined as an actor and was soon handed the artistic reins. A year later, her bold and grizzly interpretation of The Red Shoes led to shows in the West End and a UK tour. It also affirmed Kneehigh as a touring company as well as Rice’s reputation who would go on to become artistic director at Shakespeare’s Globe.

Fast forward to the present day and Kneehigh now play to between 100,000 and 200,000 people nationally and internationally including New York and Los Angeles; it seems a long way from village halls, schools and quarries. Shepherd, at 65 still performs on-stage today and remains Artistic Director.

“People are quite surprised by these figures,” says Charlotte Bond Kneehigh’s General Manager, “We’re still a small company. We have a core staff of 12 but employ freelancers in different capacities for different projects but we think of ourselves a UK company. Our rehearsal space and office are still in Cornwall.”

Cornish influence

In 2014, as an ode to the area, the landscape and its people the Kneehigh Asylum, a portable venue, made its debut in a large remote field. Essentially a large tent, the venue plays around Cornwall for a season each summer. Its malleable structure means the occasion is different for each performance. “We try and re-invent that experience every time we do an Asylum season,” Charlotte explains. “The configuration of the tent will change and the front of house area will change. You’re changing it depending on the show and depending on the audience who you think might come and see that performance.”

This audience connection is core part of Kneehigh’s ethos. Their style of story-telling is very immediate, Brechtian almost. Audiences are exposed to stories that Kneehigh are keen to tell, making each show an important event that often carries with it a message. “We always want to create a sense of event for our audience and we never take that sense of event for granted,” says Rice. “We always try and surprise our audiences which comes from being responsive to the world.”

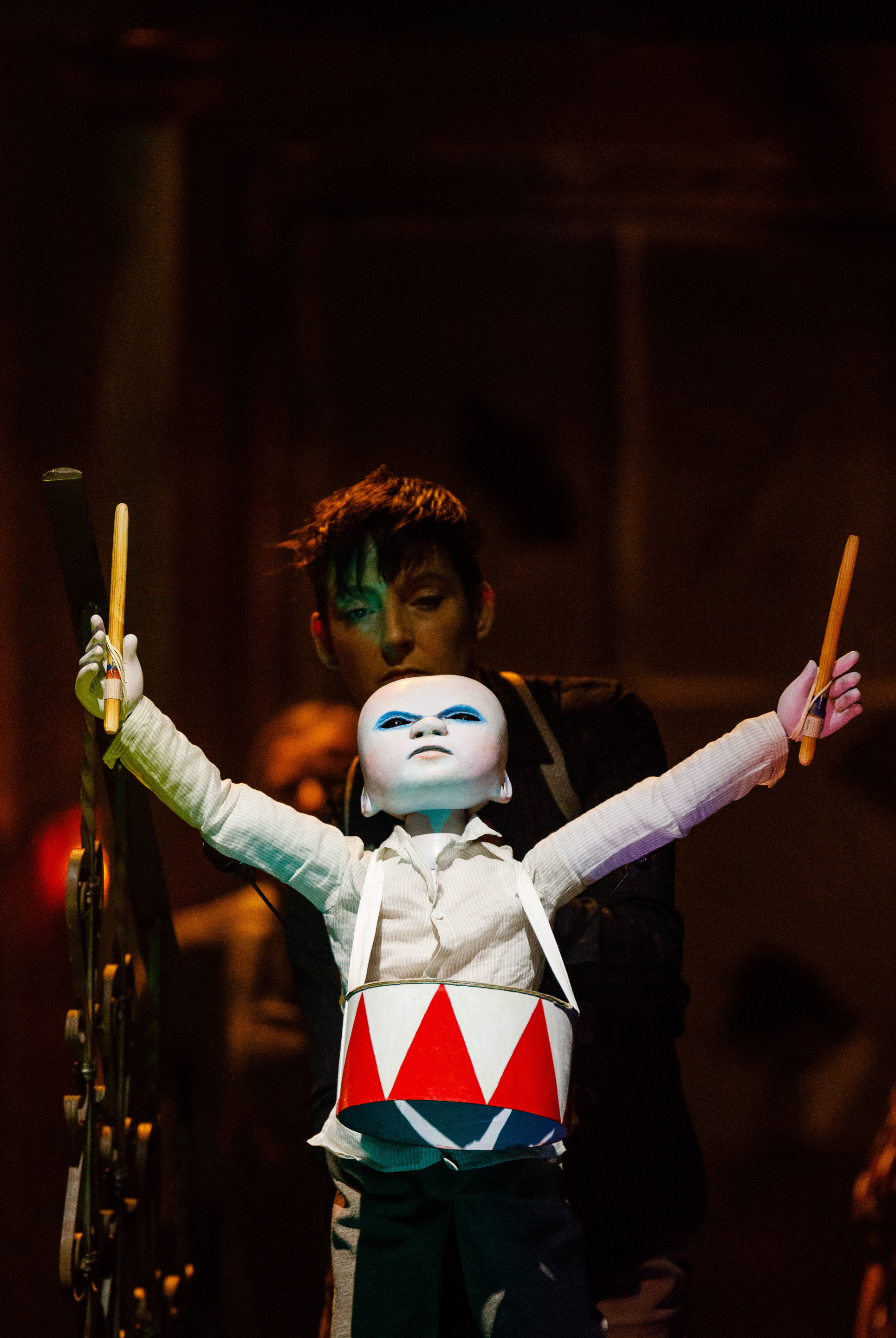

One such response is Kneehigh’s version of the Tin Drum. Two years ago, Shepherd visited the ‘Jungle’ the refugee holding camp in Calais. Here he worked alongside the Good Chance theatre company, who erected a pop-up venue in the ‘Jungle’ and put on plays for some of the asylum seekers.

Charlotte says that Shepherd’s experience in such an inhuman yet disturbingly real environment shaped his approach to interpreting Grass’ Nazi satire. “The play is very much a response to a real-world that he has experienced. I’d say it’s a call to action rather than an escapist fairy tale.”

All the ingredients

The Tin Drum, like all of Kneehigh’s productions began life as a series of thoughts, brainstorms and ideas cooked up in remote barns and outhouses on the cusp of a small Cornish village called Gorran Haven. Coastal paths splinter off from the settlement, the nearest station is half hour away by car and the majority of visitors are seagulls.

“Our ideas are always seeded in the barns,” Bond says. “It’s a great way of creating that really intense focus that you need to generate and work-up ideas. In London or other urban environments people always have something to do but in Gorran Haven, there’s nowhere to go!”

It’s this controlled yet off-the-cuff approach that really filters through in Kneehigh’s productions, where components such as music, costume and puppetry rise to the surface. Because of this their work appears on many a syllabus bringing requests from teachers and students for insight into the creative process however, as Charlotte says, this formula just doesn’t exist. “I’ve been here for ten years and we’ve always had lots of queries asking how we make the work and we’ve always struggled to respond to them,” she admits. “What we do have is a toolkit; we take an idea and with our toolkit in respond to that idea. We include things like music, lights, costumes and puppetry, so we have a selection of ingredients and we make a creative space and we essentially cook something up.”

Kneehigh’s audiences are often made up of school groups, however pupils scribbling while Mike is performing should be wary: “Mike gets really cross if people are taking notes when he’s acting. He feels that it stops people from interacting with the show and has often taken exercise books off students!”

To counter such incidents and to satisfy intrigued Kneehigh followers, the company produces an online education portal called the Kneehigh Cookbook. The visually driven, interactive mini-site encourages people to discover its many different creative elements such as lighting, production and design but never tells people what to do. “It’s about mixing and matching and trying things out and seeing where stuff takes you,” Charlotte says. “But ultimately it’s about a group of people making something rather than a style sheet.”

Community engagement

The Cookbook came from overwhelming interest in Kneehigh’s output, however there are many people from Cornwall who are unaware of the company, and unaware that theatre is something open to all. Like most parts of the United Kingdom, Cornwall has its share of deprivation. The edges remain wealthy and affluent but it’s the ex-industrial towns in the centre (Cornwall has a rich mining history) where engagement in the arts is very low. It’s here that Kneehigh, working with charities focus their outreach often inviting groups to come and visit the Asylum over the summer period.

At the same time, these areas are often rich in history and offer a wealth of stories from it residents. The Kneehigh Rambles is a typically creative form of community interaction that sees the company’s long-term writer and poet, Anna-Maria Murphy physically walking the lesser-trodden paths of Cornwall, listening to the stories of people that she meets along the way. From this, Anna will re-work the anecdotes, creatively exaggerating them into weird and wonderful yarns that feed into just as weird and wonderful videos that are hosted on the Kneehigh site.

The Rambles extend beyond Cornwall, and given the strong relationship the company have with the West Yorkshire Playhouse and their community engagement programme, Anna was invited to take her note book to the streets of Leeds meeting third generation Irish, members of the Carribean community and a man from Ghana waiting to see if his asylum application was going to be approved. “Sometimes,” Charlotte says, “Anna doesn’t need to exaggerate these stories at all, sometimes they just tell themselves.”

It’s a sentence that seems to sum up Kneehigh. There’s a pride in the lack of formula and rigid approach they take; that sometimes stories, much like the Cornish environment they are cooked up in, will occur naturally and beautifully and be all the better for it. Perhaps it’s an approach we could all think about.