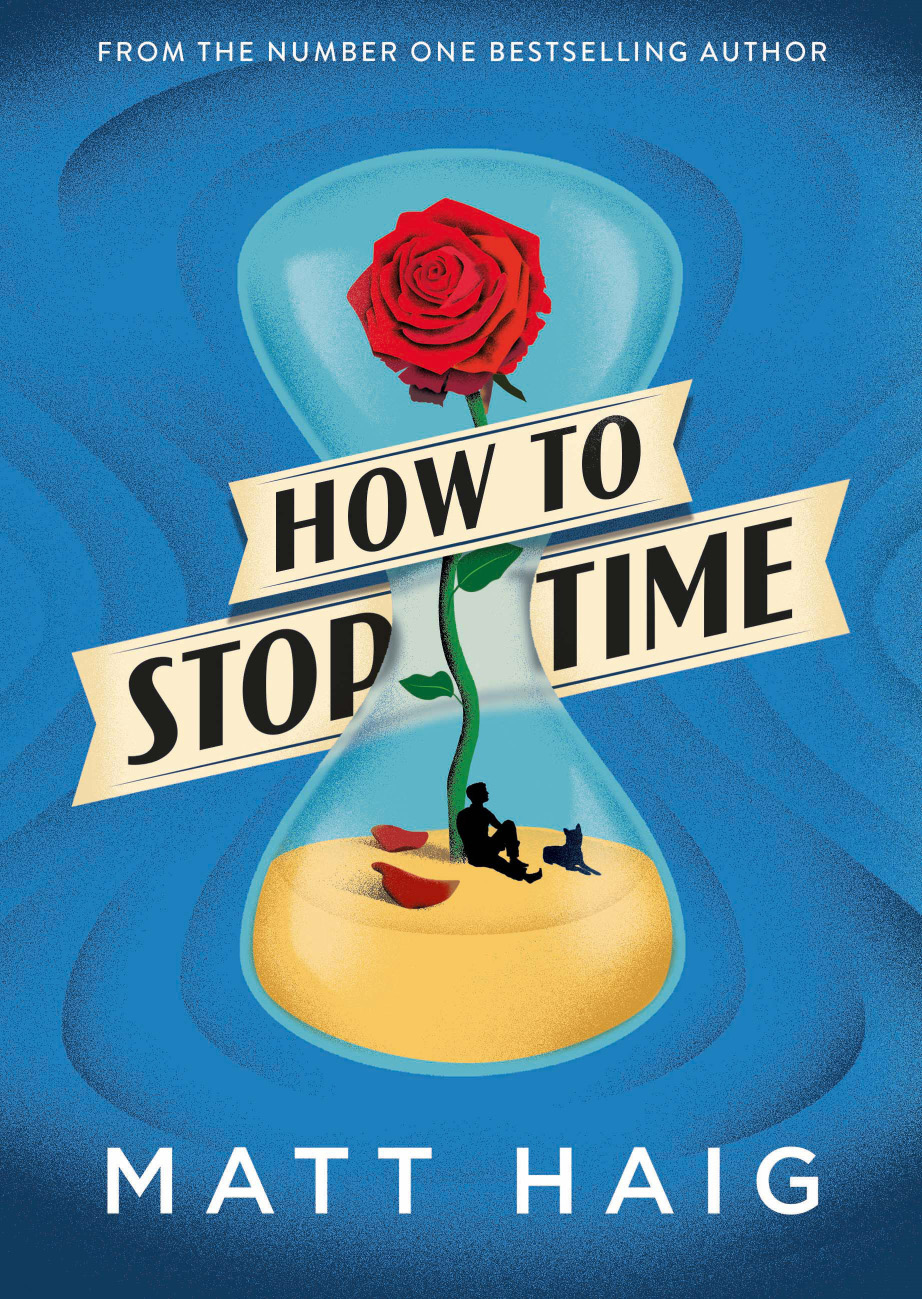

By Matt Haig

Published by Canongate

When I interviewed Matt Haig for September’s edition of Ink Pellet I was struck by the writer’s belief in the power of story-telling and how it can help young people understand the fragility of life. His fiction (Matt writes for both children and adults) pushes the boundary of the form while always coming back to what it means to be human in rather complex worlds.

His latest novel, How to Stop Time, is a case in point. The central character Tom Hazard is a seemingly ordinary middle-aged history teacher in South London except for one thing, he’s 439 years-old.

Tom is one of a select view of people who have a (fictional) condition known as anageria; where the speed of ageing slows down with Tom ageing one year for every fifteen. “I have to say it can feel like you are stuck for ever when, according to your appearance, only a decade passes between the death of Napoleon and the first man on the moon,” Tom admits early on in the book.

While the book takes us and Tom through some of the major periods of history; from the Elizabethan era to Shakespeare’s Stratford, what seems like an extremely exciting condition to have (who doesn’t want to live forever?) soon becomes a nightmare.

At the end of the 16th century at the height of witchcraft paranoia, and on the basis of an 18-year-old Tom still looking ten years younger, his Mother is accused of being a witch. Her trial, to see if she survives after being tied to a chair and lowered into a pond, of course ends in her death and is all seen by a desperate Tom.

Those handful of people that have angeria are seemingly protected, we learn, by a sort of organisation. Each person (known as albatrosses) are set-up with a series of short lives to act out; Iceland or Sri Lanka, anywhere they want to go. The cost however is a repression of feelings, and in particular love. “No falling in love. No staying in love. No daydreaming of love. If you stick to this you will just about be okay,” says the mysterious Heindrich, the leader of all the albatrosses.

Of course, Tom is extremely flawed; he struggles – as we all would – to constrain these feelings and as the story goes on we learn of his many experiences over his long life that have come to shape him and make him the person he is, just as the experiences of our 70 to 80 years on earth, shape us.

Like Matt’s previous book The Humans, this is a warm-hearted, thrilling and life-affirming read and one perhaps to share with your class. The time travelling narrative is fascinating -the description of Paris during the jazz age, for example, is brilliant – but at its centre, despite his age, like us, is a man who just wants to be human and feel everything that comes with it.

Review by Susan Elkin