Graham Hooper leads us through several of the major photography exhibitions running in London and finds he sees the world differently as a result.

I have to admit that I’m not enormously fond of London. I travel there relatively frequently because it has lots of big art museums and galleries that I love to spend time in, but otherwise I often find it busy and anonymous. On a recent visit though I started to see it differently; I found myself warming to it much more. Oddly the very things that make it so appealing to foreigners and the sight-seers London – the red phone boxes, double-deckers buses, black cabs and west-end theatres – felt charming in a way they hadn’t previously. Nothing had changed outwardly, it just suddenly felt that bit more real and affable. What had been quite familiar had become fresh, and what felt strange was now more personable. A pleasant if unexpected experience, and the perfect state of mind for my intention, as it happened.

This spring two major Photographic exhibitions had drawn me to The Victoria and Albert Museum (South Kensington) and The Barbican. Interesting it is a body of work on display in both shows that has left me reflecting on the power of Photography to record time and place so accurately and sensitively. The Paul Strand Retrospective at the V&A (“Paul Strand: Photography and Film for the 20th Century”) is an enormous overview of one America’s great father figures of the medium. Starting with his early turn-of-the-century modernist studies of machine parts, the city and natural forms it goes on to document his entire career, through portraiture and extensive visual travelogue, ending with his final garden project. Meanwhile the Barbican hosts a show (“Strange and Familiar: Britain as Revealed by International Photographers”) curated by Britain’s best-known Photographer of the social landscape (for better or worse) Martin Parr, that showcases not his images of this fair-isle this time, but those of global standing (Japanese, Dutch and American amongst others). We see London in the 1950’s, Belfast in the late 1960’s, Glasgow in 80’s and (my favourite) ‘The North’ in the mid-naughties.

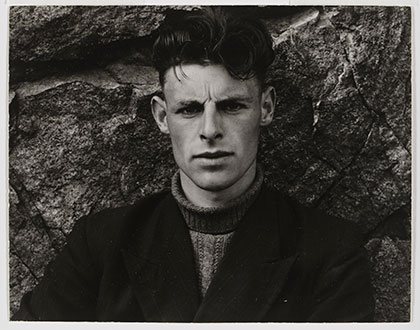

IMAGE BELOW: Angus Peter MacIntyre South Uist Hebrides by Paul Strand 1954. Victoria and Albert Museum London Paul Strand Archive Aperture Foundation

Both shows take at least half-a-day each to savour. Multiple rooms, with individual image captions and wall texts that demand careful reading, and many photographs that need to be appreciated alone or as sets before moving on. Some of Strand’s pictures are quite small (contact printed from their original perhaps postcard-sized negatives) and reward close scrutiny, whilst newer, digital images at the Barbican are floor-to-ceiling portraits with incredible detail that captivate and seduce. The displays at each are immersive in nature and truly panoramic in scope, reaching across time and space in their own ways. As exhibitions they are perhaps best approached with a rather cursory walk through, at least to begin with, followed by a slower re-visiting to hone in on particular bodies of work.

Much of the work I was familiar with as it happens. Many of Paul Strand’s best-known photographs are obviously here, but it is rewarding to see them true-scale and alongside their brothers and sisters. Parr’s show brings together rarely seen work too, but by otherwise well-known and important photographers. For instance, Garry Winogrand is synonymous with the hard-nosed New York street photography of the 1960’s but here we see his work in London from around the same time. It was disappointing, but maybe shouldn’t have been surprising, that all that really differed was the place. His quirky angles and slightly wide-angled vision, both hallmarks of his distinctive style, had been transposed to the City unchanged.

It was the consistency of Strand’s vision that made for such a pleasing and deeply affective retrospective at the V&A. Regardless of subject matter (and he worked coherently and confidently across genres, styles and approaches) his manner was assured throughout. A gentle and considered eye, he could record with dignity and respect the surface of an old stone wall just as well as the wrinkles in the hands of an elderly woman.

IMAGE ABOVE: Strange and Familiar, Curated by Martin Parr, Barbican. Photo Tristan Fewings_Getty Images

I can appreciate that photographers from outside of the United Kingdom would be attracted to its both industrial and rural heritage, likewise our inner-city politics, and our eccentric and charming population. At the Barbican however the images they took away were what we might expect; Royal jubilees, Welsh miners and kids playing amongst concrete flats are all pictured here. There is nostalgia certainly, but how much reality? I was struck by what each foreign national seemed to bring to their lens. The Dutchman, Hans van Der Meer, has made a number of glorious photographs of local football matches. Football in The Netherlands (as in England) is a national treasure but the landscape here is sloping, contrasting sharply with the topology of his native home. Likewise, the German Axel Hütte photographed housing estates in London in the early 1980’s that with all their monochrome stark geometry look like East Berlin before the fall of the Iron Curtain. The question is did they come looking for that, or is it that just what they found? What would have really helped to better understand each individual photographer’s unique vision would have been to have had photographs from their home countries alongside those seen here – to compare and contrast. It would have made for a different show maybe, but a more responsive and more reflective study I think.

The work of French photographer Gilles Peress’ in Northern Ireland from last year could actually almost be black and white versions of Akihiko Okamura’s from the same places but during ‘The Troubles’ over forty years ago. Both had previously documented social, military and civil unrest (the Vietnam War and the Iranian Revolution retrospectively) and it shows. The images mix the humane and the brutal, a rather simplistic view at times, and neither necessarily one that Ireland would have wanted or still wants to be reminded of or show the rest of the world. Whilst all pictures are accurate and none tell the truth (to misquote Richard Avedon) this entire show sunk into tragically sensationalist photojournalism, or cliché, and that was unhelpful if not just a pity. Martin Parr’s own work, purporting to be an Englishman’s view of England has been criticised in the past for the same reason. Whilst having a mirror held up at ourselves is important, even if we do not like what we see, it should be fair and not misleading. Archetypes can reveal, but stereotypes distort.

Strand seems to have been politically motivated in his work, and left America during the McCarthy era to escape what he deemed to be an unsympathetic environment for left-leaning artists. No doubt the Outer Hebrides provided as good a contrast as any to the hustle and bustle of inner city New York. With the cold war at its height it is also more than coincidental that he should choose the site of a proposed missile base to make one of his most tender and poignant portraits of a community over a sustained period of time. The simple, homely lifestyle would have resonated with Strand, and his images are romantic to an extent, but sensitive and restrained might be a better description. The work is more than just a record of the people, it is the terrain, even the values and the history that is shown. What is particularly delightful is that he is able to balance the desire for strong compositions and an appreciation of texture with a documentary sensibility. I felt no guilt about enjoying these photographs, pondering the lives of these men, women and children alongside relishing the pictorial poetry of tone and shape.

Almost the opposite was true at the Barbican. I found myself simultaneously attracted to and repulsed by Raymond Depardon’s pictures of Glasgow in the 1980’s. Dark scenes, wet, cold and miserable and yet look at those lovely buildings and the cars; the colours and geometries that betrayed the Magnum photographers aesthetic know-how felt a little easy, cheap or disingenuous. I experienced image-fatigue rapidly at the Barbican, which was a great pity. I quickly tired of pubs, bowler hats and sweet shops. None of this was the Britain I knew or frankly wanted to know really. That no doubt shows my white, middle-class and middle aged, educated upbringing. But that makes me no less British, and my perception is surely equally valid and necessarily if we are to understand this nation state, from all sides. I want to better understand my geographical and cultural context but I don’t think this was the place. My prejudices (and no doubt those of others) were consolidated rather than challenged.

Meanwhile for Paul Strand, a very well-travelled and worldly-wise photographer, the work he made across the decades revealed the universal in the particular. He saw the shape of a leaf close up as being no less important that of the local face. They are pictures of a visual world in detail that could at times be anywhere and are everywhere. I could relate to them, they transcended any specific time and place in clever ways. So very ordinary, yet so very unusual now, as seen through a lens. Strangely familiar and familiarly strange.

Paul Strand; Photography and film for the 20th century

Victoria and Albert Museum, London

19 March – 3 July 2016

www.vam.ac.uk/content/exhibitions/exhibition-paul-strand-photography-and-film-for-the-20th-century/

Strange and Familiar: Britain as Revealed by International Photographers

16 March 2016 – 19 June 2016

Barbican Art Gallery

www.barbican.org.uk/artgallery/event-detail.asp?id=17922

Unseen City: Photos by Martin Parr

4 March – 31 July 2016

Guildhall Art Gallery, London

www.cityoflondon.gov.uk/things-to-do/visit-the-city/attractions/guildhall-galleries/Pages/Unseen-City-Martin-Parr.aspx