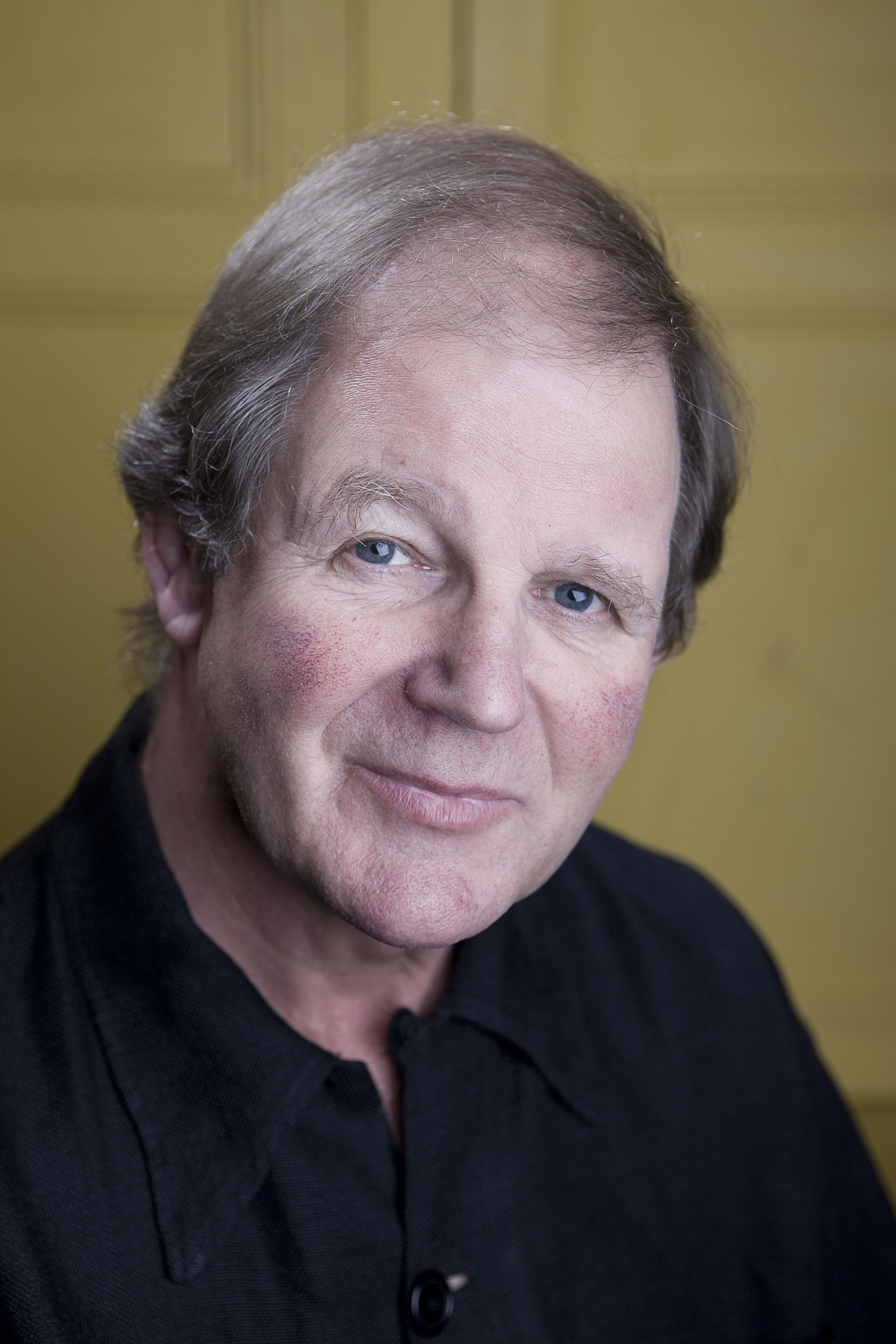

‘I NEVER cease to be surprised how my life has turned out,’ says Michael Morpurgo, which might be an odd thing to say; he is, after all, one of the most celebrated children’s authors this country has produced. But he has a point.

Softly-spoken but articulating at rapid speed, he rattles through the story of his life which certainly did not hint at the worldwide success that was to come. He took a while to settle at boarding school ‘missing home too much’ and possibly the wonderful story times with his mother. At school, he did not reach the dizzy heights expected from him: ‘I wasn’t very successful at the things I was supposed to be successful at. I found work quite difficult so I tended to do a lot of sports and singing. I left school with a couple of A levels with certainly no great ambitions to do anything connected to literature. I was thought to be good at leadership. I think school thought. ‘He’s a nice fellow, a good chap, a bit dim. The army would be good for him because people will follow him.’

So off he went to Sandhurst but at the age of 19, he realised that being yelled at by a sergeant major was not the life for him and in any case, a girl (now his wife) – Clare – came along and guided him into a decision.

He recalls: ‘I thought, I don’t like this very much and I certainly don’t want my life to be training to kill people. I backed out after a year and don’t regret doing it.’ So he went off to Kings College, London University, where he studied English and French – and ‘just managed to cling in there and got the worst degree I could possibly get.’

He then became a teacher, ending up in a tiny village school in Kent after stints in various prep schools and at last found something he could enjoy. He recalls: ‘I found my feet quite late and by accident. I got on well with the children who started to express themselves in their writing with more confidence and because of that I started writing alongside them so we would write together. I learnt about confidence in writing through teaching children to write and making up my own stories.’

Morpurgo is convinced that in order to progress, children must first enjoy reading and this is where grown-ups should step in, but this road is fraught with danger. ‘My mother used to read to me and I was very enchanted by that. School then ruined that. You can study out of existence – that is what stopped me enjoying stories when I was little because books were used almost entirely for teaching you something about literacy, which we call it now, although it wasn’t a word then.

‘The books I thought were great sources of pleasure, of wonder, and fun and excitement suddenly vanished because all the words seemed to be something you were tested on. I didn’t like spelling tests, I didn’t like punctuation and all that comprehension. I couldn’t get my head around it.

‘I do know very well now if you want to encourage children to read they have to enjoy it first. Early education should be all about pleasure so that for them a book is something they always want to pick up because it will take them off to another land. If it happens when they are young, the rest all follows. You’ve got to be able to spell, to punctuate, of course; if you wish to communicate you have to do so in a way that people understand.’

Nowadays Morpurgo, now 71, continues to write and spends a great deal of time ‘on the road’, speaking to school children, attending book festivals and taking part in concerts. On the day we spoke he had attended the Ryedale Festival and been quizzed by more than 400 schoolchildren from 27 primary schools about Private Peaceful.

The schools had come together to read the book, and then all 3000 or so pupils enjoyed the Q&A which was filmed and streamed back into their school. This he cites as an example of best practice that is becoming increasingly tricky for teachers, who are under the cosh of the curriculum.

Morpurgo says: ‘Good schools are succeeding with children who might succeed anyway because they come from homes where people read but we’re still not breaking the barrier of two million kids who simply do not seem to enjoy books. The government has got it right in thinking that literacy is critical in everything we do but they have not understood you cannot get children to become literate, to love reading and make it part of their lives unless you first make it enjoyable.’

With his name linked to the First World War thanks to the screen and stage success of War Horse and Private Peaceful, Morpurgo is relaxed about how young people reach his work. ‘What’s important to me is that they come to the book; whether that’s done through film or the stage. Books resonate for children if grown-up people make wonderful films and wonderful plays about them and then it brings them to books. It turns them into theatre goers and they think I’ll get the book; then another one by the same author; then read another and that is how it gallops.’

Morpurgo’s success has won him many awards and he is certainly firmly ‘establishment’ though he doesn’t appear so. A real champion for children, he and his wife Clare now have three farms for city children and he is President of Book Trust and Vice Chancellor of the Children’s University.

He understands the draw of technology ‘it’s stimulating, it’s fun, it’s exciting and it’s quick. Children do what most grown-ups will do – take the shortcut to pleasure!’ But his books have drawn some criticism for difficult themes of war, loss and death.

He counters: ‘Children have not changed in the slightest over the last few years. But they are learning much earlier that the world is not a comfortable place. When I was growing up nothing came into the house unless your parents wanted it to and that is not so anymore.

‘Some people have reservations about my books because they might be too sad for children – it’s a matter of when books are put in front of children. When children are very young, books are there for comfort so, for example, when the tiger comes to tea, the tiger does not eat you.

‘My books reflect that there is darkness but even when you’re dealing with it there has to be some kind of redemption. In the darkest of my books, Private Peaceful, it is grim and it is dreadful and there is a moment at the end that gives you hope and that’s important.’

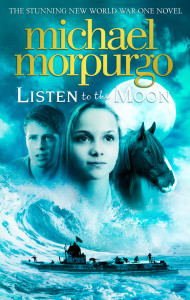

His new book, Listen to the Moon (reviewed in the last edition of Ink Pellet), returns to these dark themes. A girl is found on an abandoned island unable to speak, having suffered a trauma so deep it takes the love and patience of a family to draw it out. Based on the sinking of the Lusitania, it is story of hope and one of surprises.

Morpurgo explains: ‘The book explores how people are not what they seem to be; the doctor for instance, has great authority but is also deeply sensitive. Then you get a U-Boat captain you don’t expect him to be the kind of person who is revealed; it’s these contradictions you tease out of a story. And the story of the island being protected is true.

‘But it’s also the story of how children are affected by some of the most terrible things you could imagine; the death of a parent and how even then you can climb out of your difficulty with the help of other people. The reason why she comes out of the dark place, where she can’t remember, is because that family is supporting her, giving her the space, time and love.’

Morpurgo still enjoys writing and with this one, the story grew and grew: ‘I thought Listen to the Moon was going to be a novella but it became darker and deeper, and more difficult to get out of. Somehow the characters took hold of the book and the more I wrote the more I wanted to hear the voice of those characters which is why it’s told with so many different voices.

‘It is good when you lose yourself in the story and let it take you where it wants to go; it happened with Listen to the Moon and The Butterfly Lion. Sometimes you get into this ridiculous situation and you haven’t a clue how it will end. My best endings are because there actually is no ending. If you craft everything too tightly you retain your control of it but then it feels too pre-planned, and of course your reader will already have guessed what happens. What I loved about Listen to the Moon is you have no idea how it will end.’

The human condition continues to drive this gifted storyteller forward – even after reaching three score years and ten.

‘If you get the wrong side of 70 you do become more reflective; I reflect on what is valuable in my life – the countryside, poetry, my wife and the life we’ve had.

‘When I write, I reflect on the human condition. And the older you get, the more serious you get, and the more difficult it is to laugh at this condition. Books are so wonderful because they give young people the chance to understand about old people; boys understanding about girls, Muslims understanding about Christians; Christians understanding about Jews.

‘You can’t meet all these people; but books enable you to understand there are other people, and other places. Books are the greatest force for good that there is on this planet.’