It doesn’t take much to be disobedient nowadays – being noisy in a cinema, going in through the outdoor and sadly, the more people want me to conform, the more I want to do the opposite.

Thank heavens for artists; those defiant, rebellious individuals, uncooperative and unruly, always misbehaving. That’s how I like my art too. I want to be shown alternatives, I like being confronted with parallel possibilities, if only I were brave enough to accept their implicit invitation. Good art lets me leave an art gallery materially different from when I entered as a direct result of my experience inside.

If looking at, sensing, coming into contact with spaces, imagery or objects can facilitate different behaviour, better behaviour, then it has performed a valuable function. I would like to believe that the humble button badge, that obligatory fashion accessory of student life, small and ephemeral as it is, has the power to change lives and minds. They continue to offer a sense of solidarity between wearers, acting as a secret symbol amongst the initiated, but simultaneously provide a cute provocation to question, raise awareness and spread information in a subversive manner that is effective precisely because it sidesteps mainstream media.

But what happens when these objects, so specific to time, place and purpose, after their original context have passed to history?

Once the battle has been lost or won, what becomes of the now iconic T-shirt, so poignant at the height of the AIDS/HIV epidemic, pronouncing that Silence = Death? It appears they transform themselves into archive material, documents for museums to collect and store. Rightly so perhaps, for it is these items so easily lost to time and posterity that, being so telling of the concerns of the day, should be kept safe and secure for future generations of researchers and social historians.

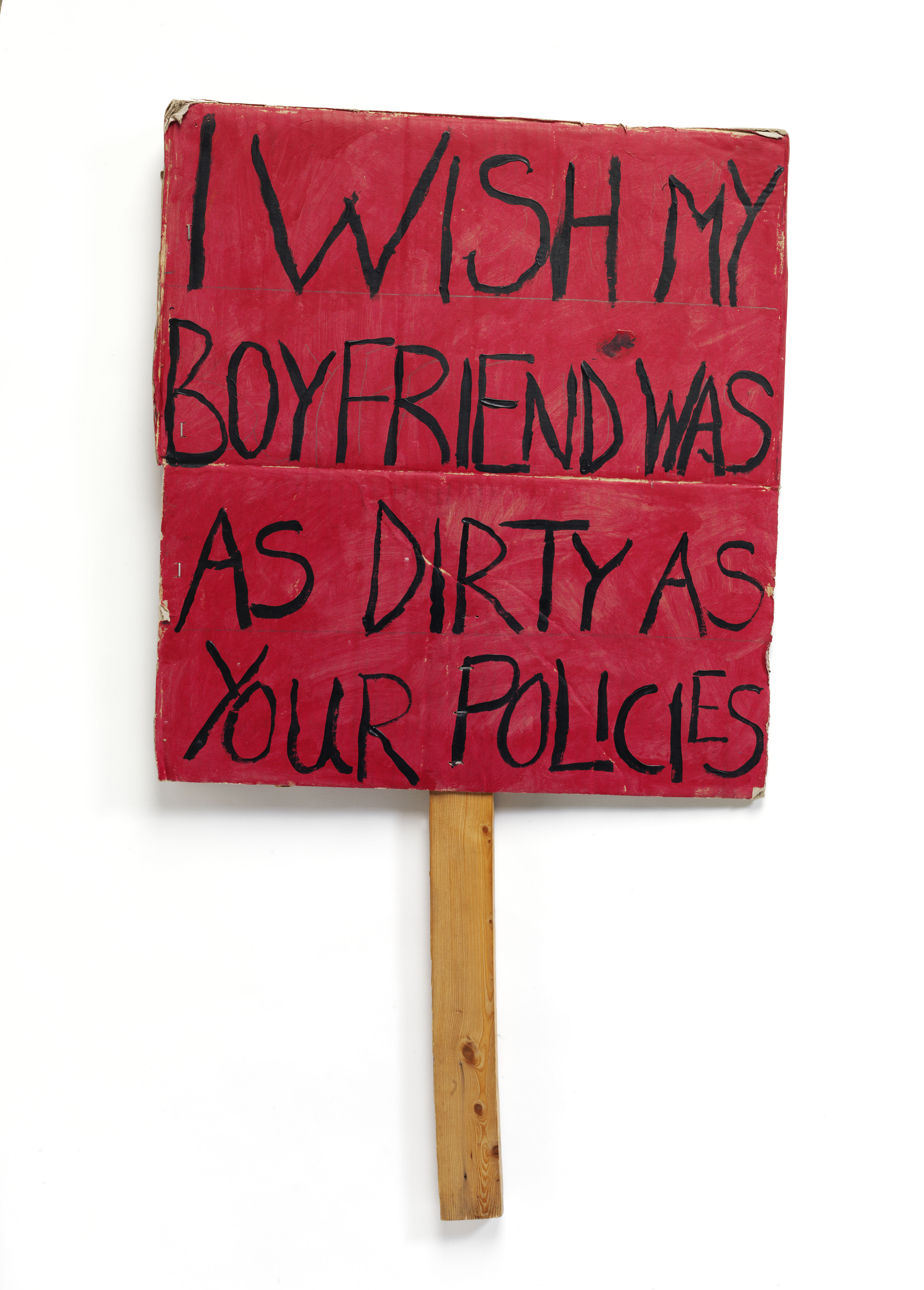

The Victoria and Albert Museum, the Nation’s treasure trove of beautiful and precious things, does not feel like a natural home for these items, but there they are, currently on display: disobedient objects; objects of protest and collective activism. Representing the last 40 years we are reminded of the ongoing role objects play in attempting, often successfully, to initiate transformative action. But housed as they are, proudly, still and silent, in their clean vitrines, accompanied by plaques explaining their context, they are nothing if not obedient. They appear even more subdued and controlled from their previous life in civil protest. They have been tamed, by the very mainstream establishment that they had worked so hard to attack or at the very least disrupt, like naughty school children forced to write an apology to the disgruntled teacher.

Crossing the road to another institution of collected and collated objects of the past, the Science Museum, we have laid out for our reflection a very different array of items. Displayed in stacks and piles we are privy to a month’s entire waste output from the museum, every single discarded item, and what a range, everything from love letters to lolly sticks have been carefully grouped for us to consider and, strangely perhaps, enjoy.

The equivalent weight of aluminium has been cast into a solid bar and every piece of plastic cutlery amassed. The effect is by turns awe-inspiring and shocking. I stood in genuine disbelief surrounded by a catalogue of various materials, at various stages of the recycling process, and personal belongings, saved from their otherwise inevitable fate.

Artist Joshua Sofaer, known for his interest in all things discarded, and for his unusual and provocative approaches to challenging public perceptions, has succeeded where the V&A has failed. If the intention was to create an environment at one and the same time immersive and powerful, I was left in no doubt as to the affect my behaviour and that of other visitors to the museum have in terms of generating postconsumer waste.

This Rubbish Collection, as it has been billed, is indeed rubbish in the sense that it is created from discarded refuse, collated for the purposes of scrutiny. However, it is anything but with respect to its profundity or transformative presence. The Science Museum is full of objects from the past that, as designed objects, represent the depth and breadth of our ingenuity and skill in solving problems, and in turn creating often dramatic social, economic and political change. The effect far exceeds what one might imagine for a display of the contents of upturned bins, and more so than the objects housed in the V&A in its ability to affect change in attitudes, awareness and most importantly, human behaviour.

Unlike the displays across South Kensington’s Exhibition Road, our ‘disposable’ cutlery and ‘recyclable’ napkins need no contextualisation or explanation in the form of information panels, and they are all the more powerful without it. This is, on the whole, the raw data, and comes across as tragically real and actual. If only our waste were more obedient, in degrading, quickly and safely, as we would like.

Conversely, it is hard to quantify the outcome of all those button badges in genuinely facilitating positive change. Other than those saved for posterity and historical reference in our great institutions, where are they now? Landfill.

Disobedient Objects, Victoria and Albert Museum, runs until February 1st. The Rubbish Collection is now sadly closed but to find out how the collection came about, visit the brilliant and informative website www.joshuasofaer.com Opening in the Science Museum’s Media Space gallery on December 2nd is Drawn by Light: The Royal Photographic Society Collection, the first major London exhibition celebrating the treasures of this world-renowned collection. The exhibition features images by some of photography’s most distinguished practitioners including Talbot, Fenton, Coburn and Stieglitz. Runs until March 1 and then opens at the National Media Museum in Bradford from March 20-June 21. For further details visit www.sciencemuseum.org.uk/drawnbylight.