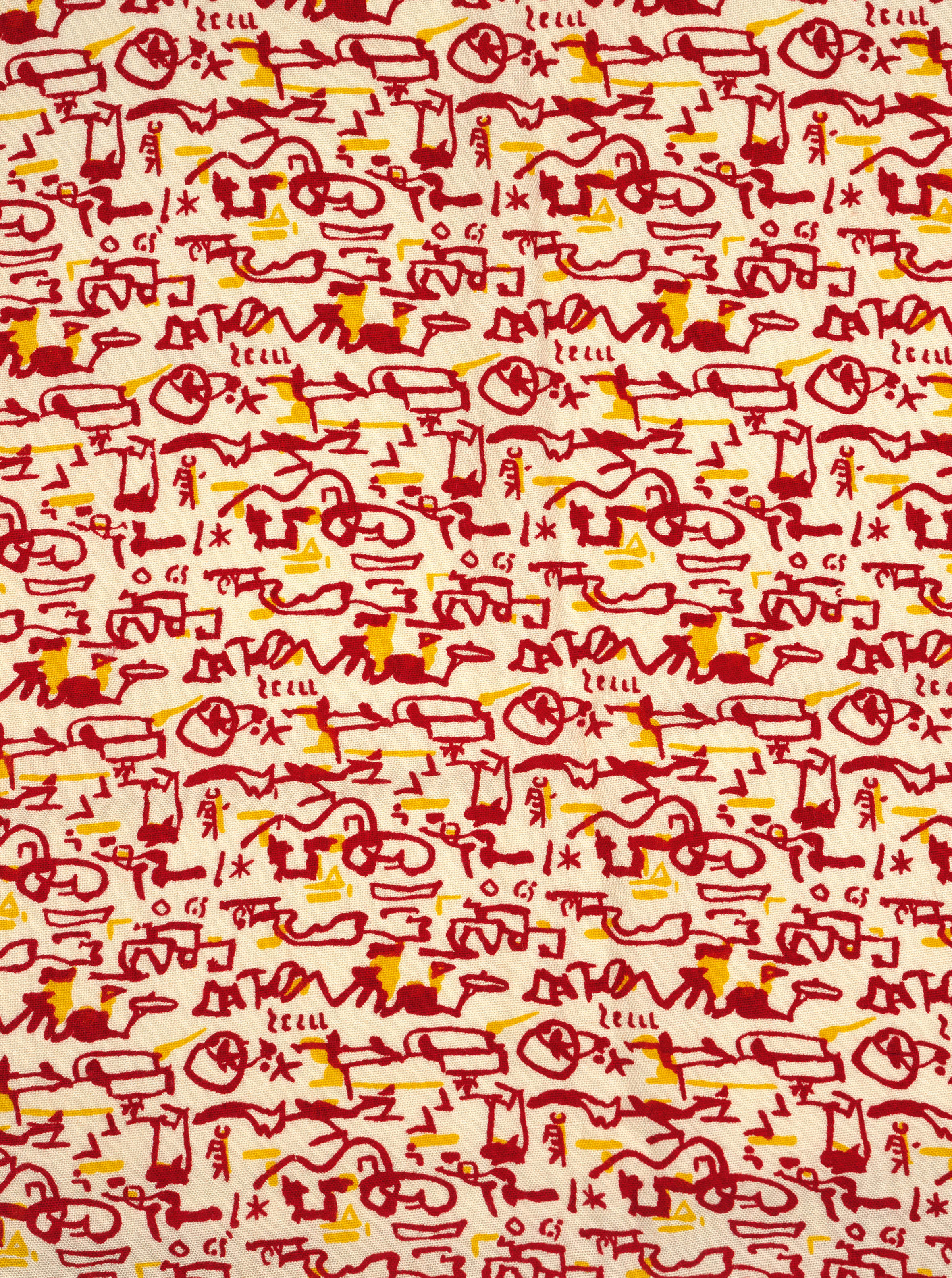

Image: Patrick Heron Aztec Small © The Estate of Patrick Heron Image courtesy Katharine and Susanna Heron

Tate St Ives must be one of the loveliest art galleries in the country. Beautifully designed, it certainly is photogenic with its toothpaste-bright façade, smooth curved stairwell and block glass panels.

But how sad to say that a recent visit left this day-tripper feeling short-changed. Guiltily admitting my thoughts to acquaintances, I found they too felt the same of their Tate St Ives experience.

Maybe it was the subject: the Summer 2013 exhibition which gave over a room each to seven key artists linked to the St Ives colony in the 20th century. For those in the know, this might be great. But St Ives in the summer is a haven for day-trippers; who, while keen to bask in the light of art of national importance, might not yet be quite knowledgeable enough to decipher the hidden messages of a work featuring a few lines and boxes, in the case of painter and sculptor Marlow Moss.

There was little in the way of explanation about the works to bring them alive; the accompanying exhibition programme was lazy – no attempt was made to enlighten the unknowledgeable about the artist with biography or proper explanation of what the art is all about.

So, to the exhibition. The artists featured included work by Moss, who settled in nearby Lamorna Cove, a beautiful spot on the south coast. Now known as one of Britain’s most important Constructivist artists, the androgynous Moss lived an unusual life, changing her name from Marjorie to the more masculine Marlow and conducted a long lesbian lover affair with her married lover A H Nijhoff. Moss’s work attracted the attention of Piet Mondrian for her ‘double-line’ paintings. In the programme there is a quotation from Nijhoff who said of Moss’s work: ‘Most people still view the non-figurative composition of our modern painters as pure mumbo-jumbo…This new art, which only a few people yet understand, makes humanity once more humane.’ Plus ça change…

My companion and I did enjoy the clever video installation by Nick Relph Three Stryppis Quhite Upon ane Black Field 2010 (though the title is somewhat irritating to type). Relph juxtaposes three films, each in a single colour and projected on top of one another so they merge and blend – clashing soundtracks, narrative and register. The films used are a documentary with painter Ellsworth Kelly, a Japanese film about the fashion designer Rei Kawakubo’s company Comme des Garcons and a history of tartan in Scotland.

The room featuring works by Patrick Heron was by far the most successful. As well as displaying his eye-catching and vibrant prints, there was a story to be told with archive letters, showing his relationship with his father who was ‘tremendously supportive’. Heron Senior said of the Aztec design that it is ‘by somebody who’s deeply immersed in modern art. The most extraordinary squiggles as motifs scattered over the surface. Each informed the other, though he was developing and learning as a painter when he began to produce designs Young people were offered a couple of activities on the day – ‘talking art’ which encouraged them to record their responses to the gallery experience and I Spy Tate, in which my usually attentive and open-minded young companion lost interest when it was unclear whether the Diamond or Quartered Diamond was featured. This is supposed to be fun, for goodness sake.

More interesting was deciphering the local references and having a good browse around the shop. Tate St Ives really needs a permanent collection (beyond the wonderfully weird Barbara Hepworth Sculpture Garden) to keep the customer satisfied. However, change is on the cards with a development programme which will almost double the gallery space. This will create the capacity for three separate zones for exhibitions and displays, enabling a year-round programme which will include a 12 month display of the St Ives Modernists and displays drawn from the wider Tate collection. Work is due to start at the end of this year with an opening date of 2015 planned.

Summer 2013, which also features work by Linder, Hepworth, R H Quaytman and Allen Ruppersberg, runs until September 29 at Tate St Ives.