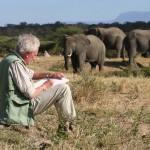

David Shepherd is one of those unusual artists who has achieved recognition and acclaim in his lifetime. Many of us remember still afternoons in the homes of grandparents gazing at a print of an elephant in the African bush – depicted with such clarity you could almost hear the swish of the great creatures.

But Mr Shepherd, who has been dubbed our greatest wildlife artist, is also renowned for his work on aeroplanes and steam. His varied work is being celebrated in an exhibition at the Royal West of England Academy in Bristol. Called David Shepherd: A Crazy Life of Steam & Elephants, it features over 30 unseen works selected from the paintings that hang in his own home. The exhibition showcases the breadth of subjects close to David’s heart – steam railways, aviation, wildlife and portraits – giving a glimpse into the ‘crazy life’ of one of the UK’s best-known painters.

He has come a long way since his childhood in Hendon, on the outskirts of London. One of three children, he was eight years old when World War II began in 1939 and was a child of the Blitz. Neither of his parents were artists. David recalls: ‘I used to watch the air raids and the ‘Battle of Britain’ on the way to school. It was so exciting – we didn’t realise people were killing each other.’

But deep inside the London lad was a burning wish to become a game warden. With a determination that has characterised his life and career, he decided to do something about it. He recalls: ‘My ambition was to be a game warden, so when I’d finished my education at Stowe, I went out to Kenya believing I was God’s gift to the National Parks. I knocked on the door of the Head Game Warden in Nairobi and said, ‘I’m here, can I be a game warden?’ I was told I wasn’t wanted. That was the end of my career in three seconds flat.

‘Up to that point, my only interest in art had been as an escape from the rugger field. The game was compulsory at school and I was terrified of it. I fled to the art department where it was more comfortable and painted the most awful painting of birds.’

But it was images of birds that would change the course of his life. With a giant flea in his ear, David withdrew to Malindi on the Kenyan coast where he took a job as a hotel receptionist. He supplemented his one pound a week wage with selling his pictures of birds at £10 a go, which paid for his passage home.

He recalls: ‘Arriving home, I was penniless and had two choices. I could either become an artist or a bus driver. I suspected that most artists starved in garrets, life as a bus driver seemed the safer bet. But my dad was marvellous. He said that if I really wanted to be an artist, I’d better get some training. The only school we knew anything about was The Slade School of Fine Art in London, so I sent them my first bird painting. They turned me down, saying I had no talent.’

It was then that a chance meeting changed the course of his life. David was at a party when he was introduced to Robin Goodwin, a professional painter who specialised in portraits and marine subjects. He recalls: ‘At that time, he wouldn’t take students but agreed to have a look at my work. The next day, I trotted up to his studio in Chelsea with that very first bird picture, and, for reasons that I have never been able to understand, he decided to take me on. I owe all my success to that man.’

But it wasn’t an easy journey – and in a way thank goodness because his story will resonate with any would-be artist. David recalls: ‘The first half-hour I had with Robin ended in tears. He told me, “if you think that because you’re creative you’re different, and you can only work when you feel like it, you can shove off. Artists, like everyone else, have to work eight hours and more a day, seven days a week, to meet their responsibilities.”’

And that told him. ‘Robin never said anything complimentary about my work and he knew just how far to push me. Once I stormed out of his studio, determined never to return, but he leaned out of the window and called down to me in the street: “Don’t be such a coward – I’m still teaching you, so you can’t be that bad!’

Once trained. David began painting aviation pictures, inspired by his love of the planes that flew over London when he was a boy. ‘I got a permit, which gave me access to Heathrow Airport. In those days it was a friendly place, not the concrete jungle it is now. I could go almost anywhere I wanted, and lovely old planes like that became my subjects.’

Because of his training, David was well suited to painting aircraft because he had been taught to be accurate, while avoiding the pitfalls of making a painting look like a photograph. He won a commission from the chairman of BOAC, and was then flown to Kenya by the Royal Air Force.

David says: ‘Again, my life changed course! When I arrived they said to me, “we don’t want paintings of aircraft. Do you do local things like elephants?”And that’s how it all started.’

He sold his first wildlife painting – of a rhino – for £25 and his career took off. A vast gallery of work has won him international acclaim but his art has allowed him to indulge his lifelong passion of conservation. It was his 1962 painting Wise Old Elephant that allowed him and his wife to buy an old farmhouse in Surrey where they brought up their four daughters.

As well as continuing to paint, David has become an outspoken advocate for animal conservation through his charity The David Shepherd Wildlife Foundation (DSWF). He says: ‘Since time immemorial, one species became extinct every century. Today, one becomes extinct every hour. With less than 0.5% of the billions donated annually to animals, and even less to core conservation projects, conservation work needs money today – tomorrow will be too late.’

In addition, David has supported the Royal Air Force Benevolent Fund by painting a picture of a Lancaster bomber called Winter of ’43, Somewhere in England. He donated 850 prints, all signed and numbered, which raised £96,000 for the charity.

Looking back, David considers his good fortune with some humility: ‘The greatest thrill of my life is to be able to repay in fair measure the debt I owe to the animals I paint and which have brought me such success. We all have a debt to pay for our stay here. This is mine.’

A few of my favourite things

David continues to be exceptionally busy – not only in painting every day but ensuring his conservation work reaches as many people as possible. The David Shepherd Wildlife Foundation raises awareness about conservation issues and has given away over £5 million in grants to wildlife projects.

So what time does the artist have for leisure and pleasure? Here we ask about David’s favourite things:

PAINTING: Waterloo Station by Terence Cuneo

Artist: Rembrandt

BOOK: I don’t have time to read but if I did then the Land Rover Handbook would be my choice!

Music: Mahler’s 8th Symphony

TELEVISION: When I do watch I like The Vicar of Dibley

RELAX: Painting!