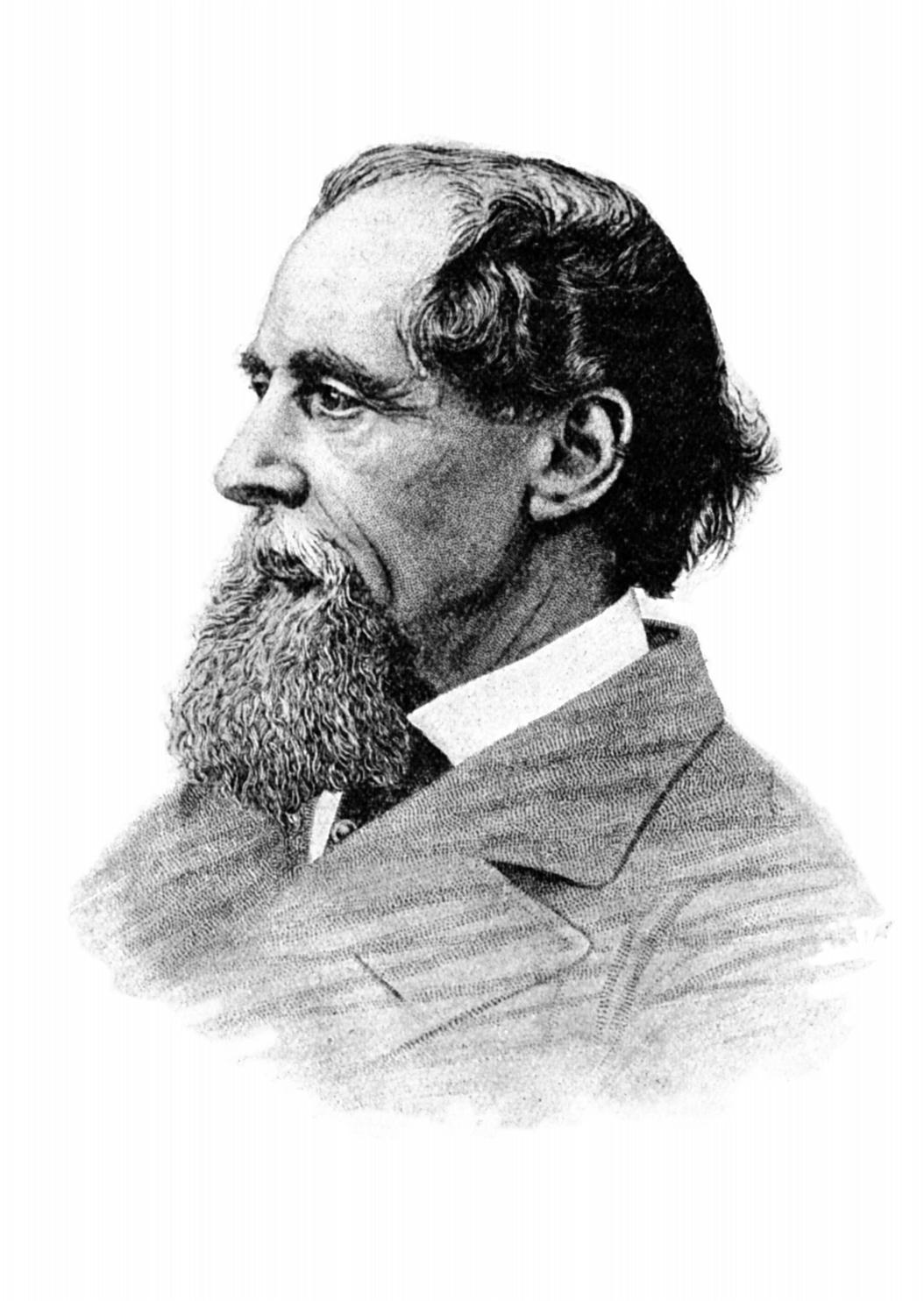

Image: the life and work of Charles Dickens will be celebrated next year

By Lesley Finlay

As this great country of ours goes through another period of social change, it is appropriate perhaps that over the course of this academic year we will be celebrating the life, works and legacy of Charles Dickens. The author is an exemplary example of the transformational value of education, his influence is everywhere today. Dickens lived in the time of the biggest social revolution to take place in Britain, as society learned to adjust to the Industrial Revolution, just as today the world is struggling to adjust to the power of the internet.

But in Dickens’s time change was unprecedented – deep poverty was pitched against great wealth; a middle class was born; a down-trodden working class toiled in the vast coal and ironworks; hyper-productive cloth mills employed hundreds in Lancashire and Yorkshire while changes in transport thanks to steam railways quickly progressed from being the new pulling power to a means of transporting people, just five short years after the Stockton-Darlington railway opened in 1825.

The effect of the industrial revolution, which began around 1760, would create a new kind of city life, with its stark social divides which echo through our lives today. While the new mills brought wealth to many, they also created a slum class. Workers would be at their posts – in the mines, at the mills, for 12 to 14 hour days with a break of one hour. But despite the squalor, country folk would continue to flock to the cities and towns – money was more regular, even though the living conditions were shocking. Solutions to these social problems heralded the dreaded workhouse, parliamentary reform and the Ragged School movement, which offered basic education to poor children.

Any study of Dickens cannot ignore a gallop through history because as well as documenting this new society in sharp detail, he did so by creating some of the most memorable characters in our literary canon, and helping to influence positive change. Perhaps this is why the writer’s 15 novels continue to be relevant today. So how and why did Dickens become such an influential and successful figure?

Born in Portsmouth on February 7 1812, his early life was marked by poor health. Charles read a great deal, and also visited London to see the pantomime and would often attend travelling fairs in Rochester, near the Chatham home to which the Dickens family decamped from Portsmouth in 1817. Five years later, the family had moved to London, where they faced severe financial problems because John Dickens (father) was somewhat frivolous with the cash. The consequences affected Charles in two ways – firstly, in order to bolster the family finances, he was employed in a blacking factory, working from eight until eight and in 1824, John Dickens was imprisoned at the debtors jail, Marshalsea. Charles, and his older sister Fanny, remained in lodgings but visited the prison on Sundays. That May, Charles’s grandmother died, leaving a substantial legacy that freed the family and set Charles back on the path of education, which was again short-lived, because of financial difficulties. These events remained with the author, leaving him with an understanding of poverty and a belief in the power of education that would reappear in his novels, as we know.

Dickens took his first job in a lawyer’s office, and inspired by his father, who had become a parliamentary reporter, learned shorthand and this led him to a career in journalism.

He became a general reporter and this set him off on his writing career. The first pieces he wrote, Sketches by Boz, were commissioned by his editor George Hogarth, and were quickly followed by The Pickwick Papers. In 1836 Dickens was obliged to resign from the newspaper, to concentrate on his writing. He was a literary superstar, travelling to America, where he was feted, and visited Europe, finally settling in Gads Hill Place near Gravesend. He became estranged from his wife Catherine in 1858, and began an affair with the actress Ellen Ternan, a relationship that was only first documented by the writer’s daughter Katey in 1939. The author died on June 9 1870.

So this potted history will begin a series of pieces about the author in Ink Pellet, as we join in the bicentenary celebrations taking place around the world next year. The focal point is Dickens 2012 (www.dickens2012.org), which is bringing together events taking place around the world. A spokesman for Dickens 2012, said: ‘Although a writer from the Victorian era, Dickens’s work transcends his time, language and culture.

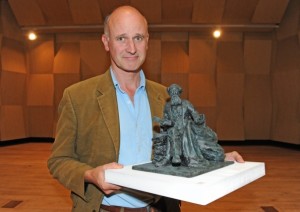

Image: Martin Jennings with his Dickens statue

He remains a massive contemporary influence throughout the world and his writings continue to inspire film, TV, art, literature, artists and academia. Dickens 2012 will see a rich and diverse programme of events taking place in the run up and throughout the whole of 2012.’

A host of organisations are marking Dickens’ work in a variety of ways. Currently number one in this researcher’s book is the Dickens Half-Marathon, taking place in Houston, Texas, in June. Organised by Rice University, the 13 mile race is open to all Dickens enthusiasts.

Portsmouth has already started planning events – including stirring up a rather polite ‘war of words’ over the plans to build a statue to the author in the town of his birth, even though Dickens once said he did not want any kind of ‘monument, memorial or testimonial’ to be erected after this death. Whatever, as they say in the playground. Dickens wanted to be buried in the graveyard of Rochester Cathedral but ended up in Westminster Cathedral, and millions of words have been written since on his art which constitutes a testimonial. The project by the Dickens Fellowship has the backing of the Dickens family.

School children have been filling up ‘time traveller’ passports for a time capsule created by local artist Deborah Dodsworth with pictures and information about themselves as well as what they like best about the city as part of Portsmouth City Museum’s Dickens Community Archive Project – A Tale of One City. In addition to this, libraries will be running a One City, One Read and a Dickens ‘Big Read’, taking reading opportunities into community venues.

Elsewhere, there is plenty going on in our theatres. The Life of Our Lord will be staged for the first time in a one-man production adapted by Broadway writer Jeffrey Hatcher, which will hit the West End in spring 2012. The wonderful Miriam Margolyes will star in Dickens’s Women, a one-woman stage show. Mrs Micawber from David Copperfield, Miss Havisham in Great Expectations or the grotesque Mrs Gramp in Martin Chuzzlewit are just some of the characters Margolyes brings to life in the show, which will tour the UK in 2012.

The Museum of London is running a new exhibition that recreates the atmosphere of Victorian London through sound and projections. Paintings, photographs, costume and objects will illustrate themes that Dickens wove into his works, while rarely seen manuscripts including Bleak House and David Copperfield – written in the author’s own hand – will offer clues to his creative genius.

The Watermill theatre in Newbury is presenting Great Expectations, adapted by Neil Bartlett and directed by Paul Hart between September 29 and November 5. In addition, two workshops are being held – Introducing Charles Dickens and Advanced Dickens. You can book these, as well as download education packs from www.watermill.org.uk.

For further information, make the starting point the Dickens 2012 website and follow our coverage over the academic year.