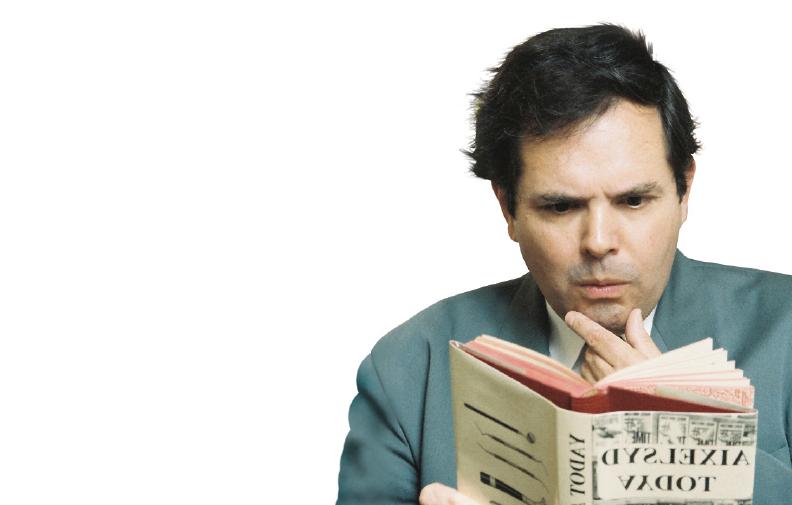

Research just published shows that many secondary school boys lack the stamina to read beyond the 100th page of a book! Now you might assume that this was yet another shocking press release from the University of the Bleeding Obvious, but newspapers and the BBC picked up the story. Once you got past the headlines, and huge amounts of indignant comment, it transpired that it wasn’t really research of any kind into pupils’ reading habits. In reality, Pearson, the publisher, had asked 500 teachers what they thought about pupils’ literacy and interests. This produced another astounding revelation that the novels of Jane Austen might put boys off reading.

Teachers were asked to identify where boys would switch off in class when novels were being read. A quarter of the teachers said the cut-off point was within the first few pages. Some 70 per cent agreed that most boys had switched off by the 100-page mark. Jonathan Douglas, director of the National Literacy Trust, commented that boys lag behind girls not just in literacy skills, but in the amount they read and the extent to which they enjoy reading. ‘This is a vital issue and one the National Literacy Trust is working hard to address,’ said Douglas. Working hard to address! The National Literacy Strategy, forced into schools back in 1998 and costing over £700 million, was supposed to solve all these problems. Seven hundred million quid and an hour of every primary school day and boys can’t get past the first few pages of a book? Exactly what did all our taxpayers’ cash go on?

It’s a fair bet that boys have struggled to engage with reading since the dawn of Eng Lit. Did Chaucer miss a trick in not writing The Teenager’s Tale? Or was this manuscript lost?

‘A Youth ther was, a Knave if truth to tell,

With matted Locks yplastred o’er with Jel.

His Speeche was surly; each and everich Minute

He cryeth out, “Wotevah!”, “Doh!” and “Init!”

For Bookes, alas, he had no tyme at all.

His loves were Drinkyng, Musik, Footy-Ball.”’

Even Shakespeare didn’t quite catch the tones of teenage boys and girls. Romeo and Juliet is not my favourite play; I find the lovers too intense and wordy. It’s time for an up-date:

Juliet: What’s in a name? That which we call a rose

By any other name would smell as sweet.

Romeo: I take thee at thy word. You’re really fit.

Juliet: How cam’st thou hither, tell me, and wherefore?

The orchard walls are high and hard to climb

Romeo: I know, my tackle nearly caught on top.

Juliet: Dost thou love me, I know thou wilt say ‘Ay’;

And I will take thy word.

Romeo: Fancy a shag?

In my first year of secondary school I was required to read Kim by Rudyard Kipling. I found it heavy going and I was hugely relieved when I got to the end. About fifteen years later, I picked up the same book and I could not put it down. With short breaks for coffee, I read the book in one go. In my list, it’s one of the top ten novels of all time. Just the first sentence is a master class of how to grab the reader: ‘He sat, in defiance of municipal orders, astride the gun Zam-Zammah on her brick platform opposite the old Ajaib-Gher – the Wonder House, as the natives call the Lahore Museum.’ In the first few words, we meet the central character as an individual who cares little for authority; we are introduced to an exotic location with strange words, then we are placed firmly in Lahore. It’s a great book, but not, I think, for 12-year-olds.

So why did Pearson ask teachers what they thought boys did when reading? It just happens that the research coincided with Pearson’s launch of a new series of shorter books called Heroes aimed at secondary boys. I’m sure they will be great books as Pearson publishes some fine authors (Well, since you ask, yes, they do publish a few books that I have written). And I suspect they are right in their supposition that boys will be drawn to shorter books. But, for me, this is yet another example of how centralised diktats, that boys should read as well as girls and that all pupils should read Shakespeare and Jane Austen, are doomed to failure. Rather than issuing even more spurious ‘targets’ wouldn’t it be better to leave it to English teachers to help their pupils find books that match their interests and their reading skills?

Keith Gaines is a freelance writer. He is a former Head of Special Needs in a large comprehensive school and Chair of Governors of a primary school.