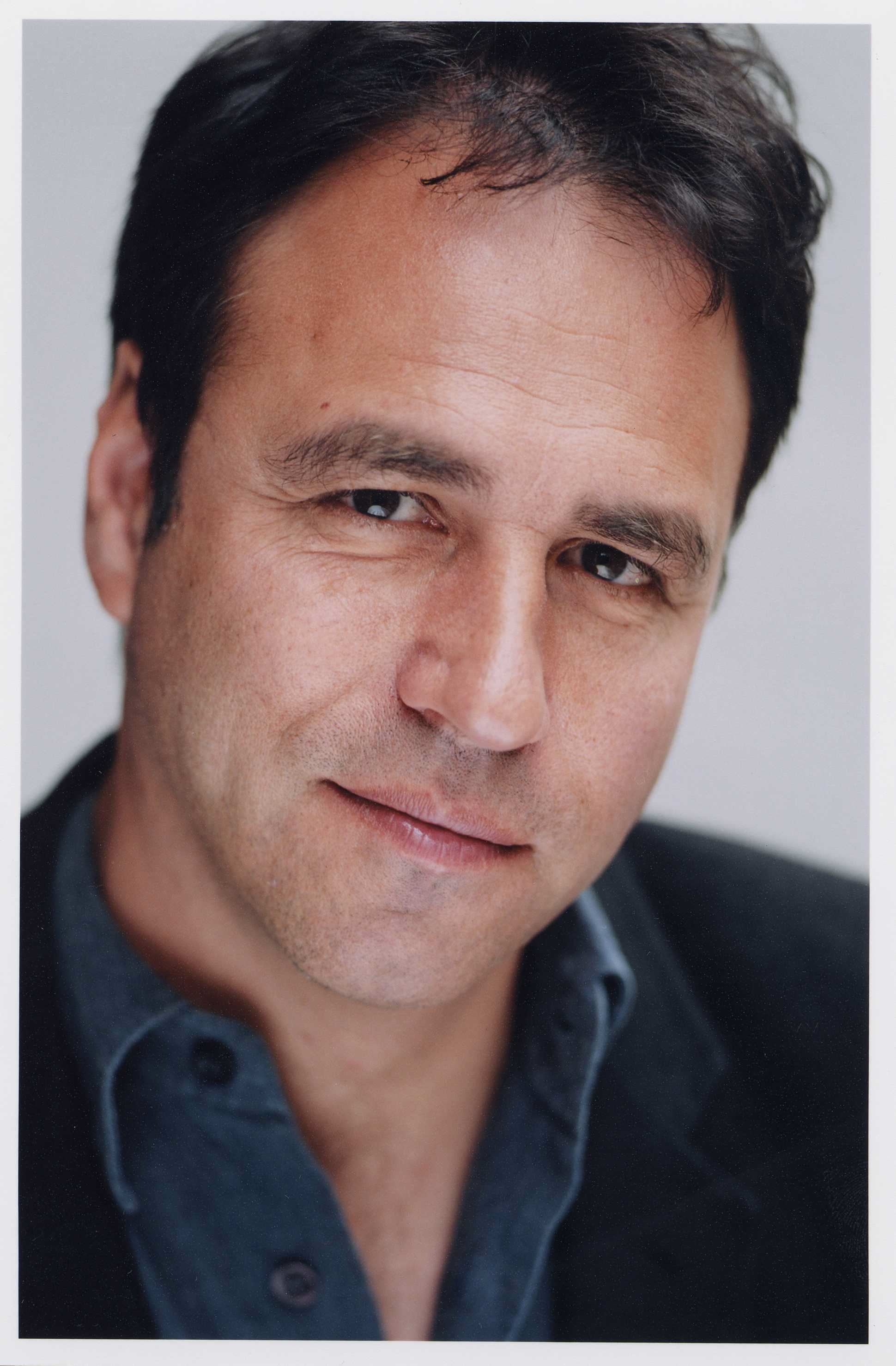

The day after listening to the wonderfully articulate Anthony Horowitz rattle through the story of his life and career for the benefit of Ink Pellet readers, a storm broke. This had nothing to do with his character Alex Rider but all to do with a, racism row’ prompted by producer Brian True-May’s comment about the lack of ethnic minorities in Midsomer Murders, the television series to which Horowitz contributed early episodes.

He was interviewed in the following day’s papers commenting in some style: ‘Brian True-May’s comments were inappropriate and should not have been made, but in our over-sensitive society there is this silly reaction to anything we say that involves ethnicity or religion.’

How right he is, but then it is difficult not to agree with his take on life, from his slight embarrassment about his bad childhood at prep school – ‘the brutality of Orley Farm made it a very unhappy time’ – to his views on the real problem with national literacy levels: ‘class is a huge part of it.’ So let us start at that dreadful experience at Orley Farm, the prep school which had a huge effect on him. He says: ‘I was there back in the 1960s when it was typical of prep schools at the time – a fairly vicious environment, destroying your morale in every way. It was a horrible place. At Orley Farm I had been educated to believe I was completely stupid, a fat waste of space.

‘The thing that saved me there was reading books. I wasn’t a particularly clever child and was quite a slow starter. I loved Willard Price and Tintin. I remember telling stories in the school dormitory – this is where I found my talent, sitting in bed and telling stories to seven or eight boys in the middle of the night. Stories were an escape to an extent, and there was a danger because I would be sent in the corridor for talking after lights out.’

At 13, Anthony moved to the sanctuary of Rugby School, a move that changed his life.

He recalls: ‘I had three wonderful teachers at Rugby and between the three of them they turned me onto literature, drama and poetry. They found the writer in me and gave me opportunities to write on the school newspaper and magazine. They taught me that there were wonderful things to be found in books.

‘You take a boy who has come out of a brutal environment and find a talent in them. Every child has some talent in them. It’s like that awful television programme Jamie’s Dream School – these seemingly horrible children are just waiting for one of those teachers to reach out to them and say “you have talent”. This is what happened to me – someone finally said, “you seem to have an affinity with books”.’

After Rugby, Anthony, aware that his life had been ‘utterly protected, safe and small’ went on a gap year which led him to Australia to work as a cowboy. ‘It was time to try to see something of the world and to give myself the challenge of doing something I couldn’t possibly do. I had never ridden a horse before, I had never chopped up cattle, I had never shot. I always say I’m the only children’s author in the business who could turn a cow into every single steak! With the money I earned I travelled back overland, a journey you cannot do any more – it took in Iran, Afghanistan and the Khyber Pass. It took me almost exactly a year – I learned more in that year than I had in the ten years before.’

And so Anthony went back on conservative track to York University to read English Literature and Art History, and then returned to London to be a copywriter. ‘I do regret this except for the fact that it is where I met my wife. I wished I used those years to test myself more and to live a little more dangerously.’

And maybe this is why he buried his head in writing. Anthony’s first work was published when he was 22 – The Sinister Secret of Frederick K. Bower. He remembers the moment. ‘Every author remembers that sense of awe, excitement and achievement and you don’t know at that time that you’re only at the beginning, that the whole journey starts there.’

Two more books followed and then came his first foray into writing for television. ‘The producers of Robin of Sherwood were looking for a story. I bought a book called Writing for Television and did what it taught me to do. To my astonishment my script was picked up.’

When he was thirty, Anthony reluctantly left advertising to concentrate full time on his writing. He worked on several television projects including Poirot, Midsomer Murders and eventually, Foyle’s War, his own creation.

Life stepped up a level in 1999 when Stormbreaker, the first in his Alex Rider series, was published. Anthony explains the book’s appeal. ‘All writing is about writing the right book at the right time. There were no spy books at the time, with a believable character and stories that were quite violent and fairly credible. I’ve always said, too, that curiously it’s to do with Tony Blair and the Iraq War. There was such an atmosphere of mistrust. We were manipulated, and this is what happens to Alex, he is being manipulated and lied to by MI6 so it was timely in that way too.’

It is an untruth universally acknowledged that Alex Rider is written for boys. Anthony is trenchant in his views on this: ‘I know the books are credited with getting boys reading. I’m absolutely delighted about that, of course. It is very important that there should be books out there that boys should enjoy but I didn’t set out to write for boys. They are written for an equal audience. I write stories.

‘There are more serious questions to ask than whether boys or girls are reading. The question we should be asking is why do wealthy and privileged kids read more than less wealthy and less privileged kids? What are children from ethnic minorities reading? Is there a divide between the north and south of this country? These questions will give you answers that are more revealing and more significant.

‘Literacy is one of the first things in the world that will allow for social mobility – if you read, have an understanding of story and culture, you’re far more likely to be in work than if you don’t.

‘The issue of reading is not at the centre of our national consciousness. If you want to see what hits home with the British public, look at the forests. The government wanted to sell off the forests and there was something visceral, something absolutely at the heart and the soul of this country that just said no. And David Cameron was smart enough to realise that he had got into the most dreadful hot water. Unfortunately, reading doesn’t quite come into that heartland.’

So what is the answer? Anthony explains: ‘If I were Prime Minister I would bring back time for reading for pleasure. I can hear teachers just laughing at me and saying where are you going to find time? But you can find it if you drop something else. And what’s that something else? Citizenship would be one of my first targets.

‘I would bring back shared texts and would make sure every child read whole books rather than extracts. I find it, extraordinary that children don’t get the opportunity to read a book from start to finish in a class because it’s a great leveller. I know I sound like a middle-aged man who went to public school but I am a thick middle-aged man. I never did well academically but the only thing that did it for me was reading. Reading gave me my life.’

There is a real sense of keen frustration that simple messages are not getting through to the right people, that good folk are preaching to the converted and somehow the message needs to get out, to a wider public debate.

You cannot disagree when one of the best storytellers of our time says, ‘The idea of doing anything for pleasure in the context of education seems almost ridiculous now.’

He is right, of course, but one is left with a keen sense of his frustration that ‘the system’ is all wrong, that he ‘does his bit’ in this ad hoc national debate, and if you can influence in any way, that is all good. But then, just as he says, we are ‘the converted’ too – maybe we need to make some noise elsewhere.

A few of my favourite things

NON-FICTION: The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich by William L. Shirer – a brilliant reconstruction about what happened in Germany

FICTION: Great Expectations by Charles Dickens. Pip is such a troubled, enigmatic hero. I find him fascinating. Miss Havisham is such a good character, and the surprises are so good.

FILM: The Third Man

TELEVISION: I liked The Promise and Lost was good although it just got worse and worse. It’s terrible how much television I watch is American.

MUSIC: I like Philip Glass and Benjamin Britten.

And you are…?

Name: Anthony Horowitz

Born: 1956 in North London

Married: To Jill Green. We have two sons.

Most famous for: So many things it’s impossible to list – Alex Rider, The Power of Five, Foyle’s War, being outspoken, advocate for reading…

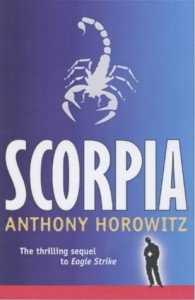

Out now: Last in the series of the Alex Rider series called Scorpia Rising

Coming soon: Sherlock Holmes novel in November and a feature film

Loves: Reading, from thrillers to 19th century literature, walking the dog in Suffolk, meeting young people on tours.

HE SAYS: Life is cheery, all in all.