Our technology literate generation owes a great debt to Nam June Paik. A major exhibition at Liverpool Tate explores his importance as JO BALDWIN and ALISS LANGRIDGE found out…

Performance and video artist, exhibitionist and visionary, the late South Korean born artist Nam June Paik (1932-2006) transformed video into an artistic medium to show the changing pace of technology now and in the future. The Liverpool Tate and FACT have collaborated in a dual exhibition to celebrate his life, work and achievements.

Paik was refreshingly optimistic about the potential technology offered for human interaction, and was possibly the first artist to use video, satellite communication and lasers in his projects. His video installations pre-empted MTV and the modern-day DIY phenomenon of You Tube by decades. Both could be said to be the ‘child’ and ‘grandchild’, respectively, of Paik’s pioneering work.

He even anticipated the internet and its explosive impact on future generations, coining the term ‘electronic superhighway’ back in 1974.

Paik’s work addresses the eventual breakdown and merging of the natural and artificial, echoed in reality by mankind’s increasing reliance upon technology. With his videos, he helped establish a new role for the artist as researcher and documentary historian. There is a sense that many of his pieces form part of a larger continuum, a lifelong work-in-progress, just like technology itself. Paik began his career as a composer in Japan and Germany. He worked with, and was influenced by, a number of artists such as cellist Charlotte Moorman and avant-garde musicians John Cage, Joseph Beuys and Karlheinz Stockhausen. Sections in the exhibition focus on his collaborations with them, shown through different photographs, documents and footage of rare performances.

Beginning at the Wolfson Gallery on the ground floor of the Tate building, the introductory part of the exhibition presents the viewer with biographical information and images of Paik, before moving on to explore around ninety works during different phases of his career. The artist’s innovative use of technology is a hallmark of the various works shown at the Tate and FACT.

Meditation and Manipulation contains some of Paik’s early television experiments such as Magnet TV (1965), an exploration of the medium’s structure. The installation includes a powerful electromagnet, which audiences at the original exhibit could manipulate to produce various patterns.

Opera Sextronique focuses on the creative outcomes between Charlotte Moorman and Paik. Their work explored the humanising aspects of art and technology, often resulting in provocative acts. Notable is Oil drums, Homage à Charlotte Moorman (1964), a version of Variation on a theme by Saint Saëns, a musical piece about a swan. Moorman plays the opening notes on her cello, before interpreting the next section by mimicking the swan’s movements while submerged in a water-filled oil drum.

The Electronic Nature section explicitly confronts the boundaries separating nature and technology. In TV Garden (1974-77) television sets are placed alongside tropical plants. The effect is beautiful, encouraging the viewer to reexamine their own perception of the organic and synthetic as distinct, irreconcilable entities.

Paik takes this theme further. In Video Fish (1979-92), seven aquariums filled with fish are placed before flashing monitors in a juxtaposition of the real and unreal, the natural and technological. This piece also raises questions regarding the way nature views and relates to us. Do the fish perceive our everyday interactions as their television?

The Robot Family section explores the kinship between familial and technological generations. The exhibit consists of several robots of varying size, constructed from television sets and other items. The television set is a gathering point of the home and might even be considered ‘part’ of the family. Like our parents and guardians, the TV is a mentor of sorts. We are ‘programmed’ to a degree by what we watch on television, just as robots are programmed by human beings.

Over at the FACT gallery, Laser Cone (1998), produced in conjunction with Norman Ballard, is a striking sculpture that connects the scientific with the spiritual. Laser light originates from crystals, often used for spiritual healing purposes. The viewer is asked to lie beneath the cone in order to enjoy the hypnotic effects of a kaleidoscopic light show. (CAUTION: this work is not recommended for people with sensitivity to flashing lights.)

Gallery 2 at FACT presents a selection of Paik’s video installations and short films. In Digital Experiment at Bell Labs (1966) the artist performs an early experiment with digital imagery by creating moving white dots and numbers against a stark black background. This historically significant piece marks the start of the digital era we take for granted today.

Also of interest is Good Morning Mr Orwell (1984). Originally broadcast as a TV special on January 1st 1984, it was the first international satellite video installation, combining innovative musical instruments, dance and performance art. There’s an optimistic and playful sensibility, in sharp contrast to the dystopian setting of Orwell’s novel 1984. Long time Paik cohort Charlotte Moorman demonstrates the curious TV Cello, while John Cage performs an unusual composition using cactus plants and a feather.

Students of art, film, media and communications will find much of value in this exhibition. The colourful and sometimes playfully interactive nature of the works will thrill younger learners too. Nam June Paik might be a relatively unfamiliar name outside artistic and media circles, but his influence on video art, special effects and communications media cannot be underestimated.

Nam June Paik: Tate Liverpool and FACT, runs until March 13. Admission £6.60/ £5.50 concessions (FACT –free)

Nam June Paik, Uncle, 1986 © Estate of Nam June Paik Photo Cal Kowal

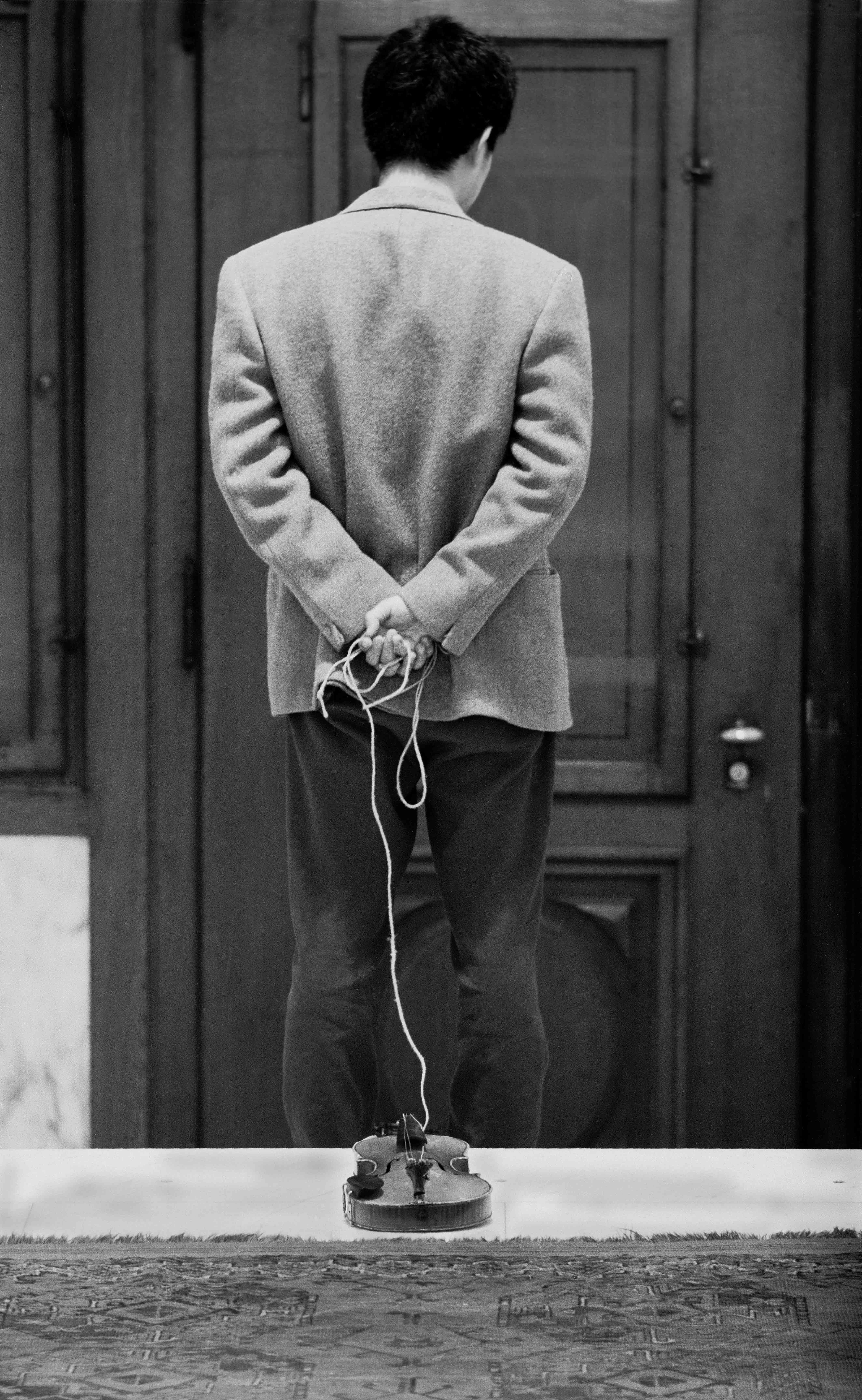

Nam June Paik demonstrates Zen for Walking 1961 © Manfred Montwé. Photo: Photo by Manfred Montwé