Should publishers adapt the classics for a more sensitive modern audience? Ink Pellet readers give their views…

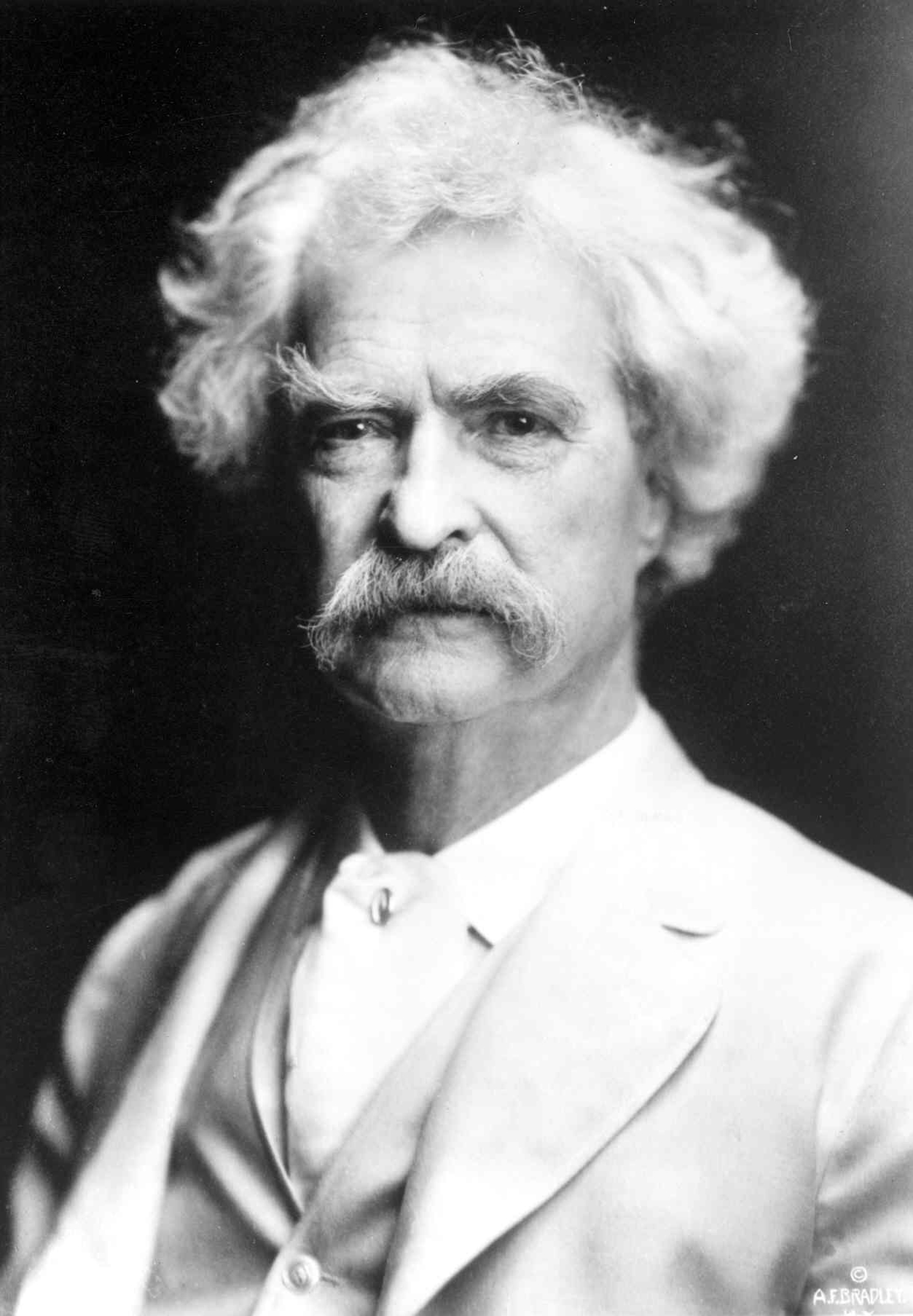

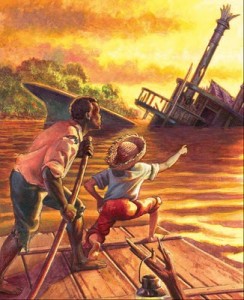

An American publishing company has revised its edition of Mark Twain’s Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. Professor Alan Gribben, a world-renowned Twain scholar believes that the language – including the word ‘nigger’ (which has been changed to ‘slave’) and ‘injun’ – prevents people having a ‘comfortable read’ of the all-American classic.

The same problem of language could be applied to a host of works – including the much-loved Harper Lee classic To Kill A Mockingbird,, which contains 58 mentions of the word ‘nigger’ and no one has complained (yet). There is no doubt that context is key as Professor Jeff Wallace, Head of English, Communication, Film and Media at Anglia Ruskin University, explains: ‘The text is a historical artefact; today’s readers should be able to see how a word was used in different contexts, even if that word is now deeply offensive. To assume that the use of this word somehow endorses it is to hold a rather simplistic notion of how a literary text works.

‘Language changes, and words are often re-appropriated, as is the word “nigger” in some contexts today. So context is all: an understanding of the offensiveness of the term today is not incompatible with an understanding of its key role in Twain’s novel.’ Twain was fiercely anti-slavery and Lee’s novel one of the finest about prejudice. Ink Pellet reviewer and teacher Robert Hill recalls his own experience of To Kill A Mockingbird. He says: ‘I was lucky enough to have an English teacher in my third year of secondary school who urged us to read To Kill A Mockingbird despite it not being a set book. He then encouraged us, a bunch of white kids growing up in a rural setting in the 1970s, to discuss the racism in the book.

‘We were left in no uncertain terms with the knowledge of the real connotations of the word nigger. This knowledge aided us in our understanding of the ridiculous concept of any set of people having superiority over another.’

Teacher Joanne Baldwin says that history has unpleasant episodes that we have to learn from.She says: ‘Classic works of literature often have a dual value as important historical documents, allowing the contemporary reader some insight into the attitudes of the period in which they were written. And history, let’s face it, isn’t always pleasant.

‘How can young readers be expected to learn from history if they’re only allowed to see the sugarcoated version? An effective teacher will be able to demonstrate that the language is a product of that period.’

Robert argues that sanitisation of literature is nothing more than pernicious censorship. ‘Focusing on the word is counter-productive for many reasons. Referring to nigger as ‘the n word’ reduces it to nothing more than a swear word or vulgar language. This is dangerous as the word has political and social connotations that cannot and should not be brushed under the carpet.’

Dr Mick Gower, Senior Lecturer of Contextual Studies at Anglia Ruskin University, agrees. He says: ‘The result of censorship would be most hurtful to the very people the censors most wish to avoid offending: school pupils and students of African, African-Caribbean and African-American descent. Denying the racism that was deeply ingrained into everyday language belittles the racism so many millions of people have suffered and continue to suffer.

‘And if we can’t come to terms, either emotionally or intellectually, with the differing cultural values of our past, how can we possibly learn to accept and learn to celebrate the differing cultural values of our increasingly multi-cultural and multiracial present?’

From a literary perspective, changing words is dangerous too. Robert says: ‘It is important that writers feel free to represent the language of the times to allow the reader the chance to analyse and debate the meanings of language.

‘Twain wrote Huckleberry Finn to show the rest of the USA (and the world) how casual racism in the USA was so deeply embedded that the users of the word nigger were able to justify their racism with a view that African-Americans were somehow inferior to whites. ‘Sanitising’ or ‘cleansing’ the word from Huckleberry Finn will dilute the message of this excellent novel and to the detriment of its impact as an anti-racist tract. The ‘thin end of the wedge’ argument is relevant here. What of Othello, Shylock and other characters in literature; will they be ‘sanitised’? It will be a tragedy if they were; both in artistic terms and for freedom of expression.’

In fact, King Lear has been subject to change, as Peter King, from Wisbech Grammar School says. ‘There is never a shortage of people who believe they have a mission to touch up the Old Masters. Thomas Bowdler set out to make Shakespeare more suitable for women and children, Nahum Tate produced a happy ending for King Lear and interferers have been loading up the Bible with inclusive language to placate the feminist lobby.’

But our more intelligent pupils will not be fooled. Peter again: ‘Greybeards in English departments currently bridling against the politically correct choice of poetry imposed at GCSE will remember how the omitted lines in The Canterbury Tales became the best known parts of the canon for curious students. Let the meddlers who know best produce texts which are better!’