Ink Pellet reviewer JULIA PIRIE was more than impressed with Nicholas Hytner’s Hamlet…

To me, the genius of Shakespeare lies in his uncanny ability to be perennially topical and this National Theatre production of Hamlet is particularly accessible.

If you don’t already agree with Larkin’s oft-quoted observation about parents’ relationship with their children, Hytner’s production might find you doing so. If Old Hamlet and Polonius had left well alone and if Claudius, having taken the crown, had concentrated his undoubtedly capable political nous into bringing the state of Denmark into line with the modern world rather than involve himself in a messy domestic, Hamlet and Ophelia could have been the prototype for William and Kate and lived happily ever after.

Vicki Mortimer’s set places you in contemporary corridors of power (neatly realised by an assortment of sliding doors) where politicians from behind desks and in front of cameras spin news stories to the media and monitor the nation’s goings-on. An ever-present team of wired and armed security guards glides in and out of the shadows, muttering into earpieces. Ophelia’s Bible is bugged for the ‘nunnery scene’. Laertes’ quest for justice seems all the more powerful in the wake of recent events on the streets of Tunisia and Egypt. On a lighter note, Hamlet’s bedroom is instantly recognisable as the student pit all mothers despair of.

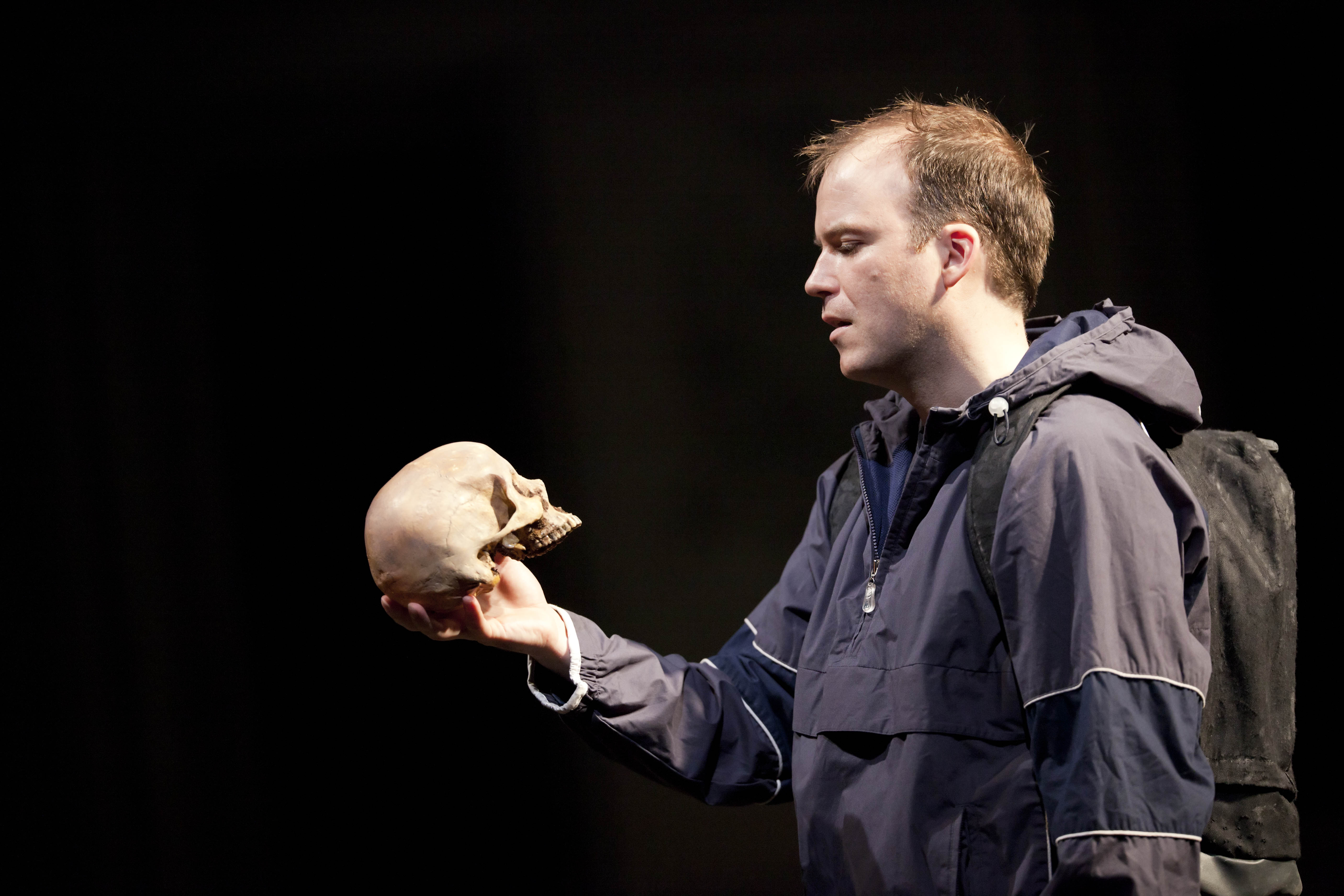

The cast delivers a strong team piece. No particular ‘stars’ here to dazzle and distract; just experienced jobbing actors plying their trade as the prince himself would have wanted. At their centre Hytner places Rory Kinnear and lets us watch a Hamlet reflected and refracted by the stories of those around him.

Kinnear is superb as the doomed prince. Forced to stay in his now alien homeland, he struggles to rationalise what is going on both around and within him. He holds the audience over three hours, fifteen minutes.

Although he plays the lighter moments deftly (this is not production without comedy), Kinnear’s strength lies in his ability to form each thought into words as if for the first time.

Students, who have puzzled over why Hamlet delays so tiresomely for five long acts, can see in this Hamlet the crippling effects of both his clinical depression and his religious belief that, for full satisfaction, Claudius must be killed in a state of sin as his father was.

Patrick Malahide plays an efficient Claudius who never asks for our sympathy. Clare Higgins is his besotted queen, tottering to her end on four-inch heels, a clever signifier of her instability from the start. Ruth Negga makes an unusually rounded character from Ophelia’s all too slight part. Way out of her depth, struggling with the demands of adolescence and systematically severed from those bonds of love which tether us all to sanity, she becomes another victim of this totalitarian society. In an innovative piece of business which was well-documented when this production opened, Claudius has Ophelia ‘disappeared’. The dramatic irony makes a mockery of Gertrude’s lyrical elegy and damns Claudius as even more of a monster. David Calder’s Polonius seems genuinely care-full of his children and not the sycophantic snoop to which some actors reduce him. However, by doubling Calder as the Gravedigger, Hytner clearly indicates where he puts the responsibility for Ophelia’s tragedy.

In an otherwise riveting production, the play within the play remained the thorny staging problem it inevitably becomes in modern-day productions. Surely the courtiers should be watching a wide-screen TV; Hamlet could be seen in the editing suite beforehand. Giles Terea’s Horatio, too, was a bit of a disappointment (at least the night I saw it). I felt he hadn’t come from the same university as Hamlet and was left feeling that Laertes might have made Hamlet a much better friend. But perhaps that’s all part of the tragedy.

Images of Rory Kinnear as Hamlet by Johan Persson