GRAHAM HOOPER explores the role children’s toys and games play in depicting conflict in the thought-provoking War Games exhibition currently on at the SeaCity Museum in Southampton.

Could it be that guns actually look the way they do because they imitate their primitive ancestors, crafted by children playing in the woods, rather than the other way around?! The very first item I was confronted with as I entered SeaCity Museum’s current War Games exhibition (Southampton, 7th February-10th May) was labelled as Stick handgun, 2012. It is a perfect introduction to “an exploration into the fascinating relationship between conflict and children’s play” with a display of objects spanning over 200 years, from the 1800’s right up until the present day.

There’s everything you’d expect in a show of this subject and scope: Napoleonic lead toy soldiers and action man figures, war-themed board games (from Risk to Escape From Colditz), 1950’s laser guns and their modern-day equivalent, the Nerf gun. Much of the material on show is nostalgic (for those of us old enough to remember G I Joe, for instance) or historically intriguing (board games that were used to smuggle maps into Prisoner of War camps during the war) but I was left feeling distinctly uncomfortable.

The display items have accompanying captions which were often illuminating (toys in bomb shelters needed to be cheap, small and portable) but being told that “war has always been an inevitable part of this world” was a frankly shocking statement to read. I spent the rest of my visit pondering whether this was really true, and it shaped my perceptions throughout the rest of my time in the gallery. I wandered around looking at objects that had been designed to celebrate heroic exploits and promote military recruitment. I discovered that, as recently as 2011, the Ministry of Defence had licensed the use of military insignia on children’s toys to ‘positively promote the military as a career option’. Inviting visitors to dress up as cowboys, vote on their favourite weapon or colour in a picture of a tank felt unnecessary in an exhibition that was already engaging and interactive enough.

The exhibition suggests that war games might help children ‘make sense of war’, if it is actually ever really possible to find ‘sense’ in the reality of armed conflict? To give the show its due credit it acknowledged the controversy surrounding children ‘playing war games’. Research appears to be inconclusive as to the effects on children. Does it make them more aggressive, or help them to distinguish between pretend conflict and real conflict (with its genuine intention to harm)? The two may not be mutually exclusive.

Some of the pieces on show were profoundly moving, as opposed to simply intriguing or entertaining. There were a number of photographs showing children playing with guns, for instance. Photographer Morgan White had captured his daughter, aged perhaps 5 or 6, dressed in army fatigues but boasting a toy gun – a big branch the size and shape of a bazooka. In fact the gender was only clear on close inspection or after reading the caption. The image, titled Mum wouldn’t let me have a toy gun, so I made my own (2010), is a big, square, black and white print that could have been taken in Vietnam by Don McCullin 40 years ago. The title said it all.

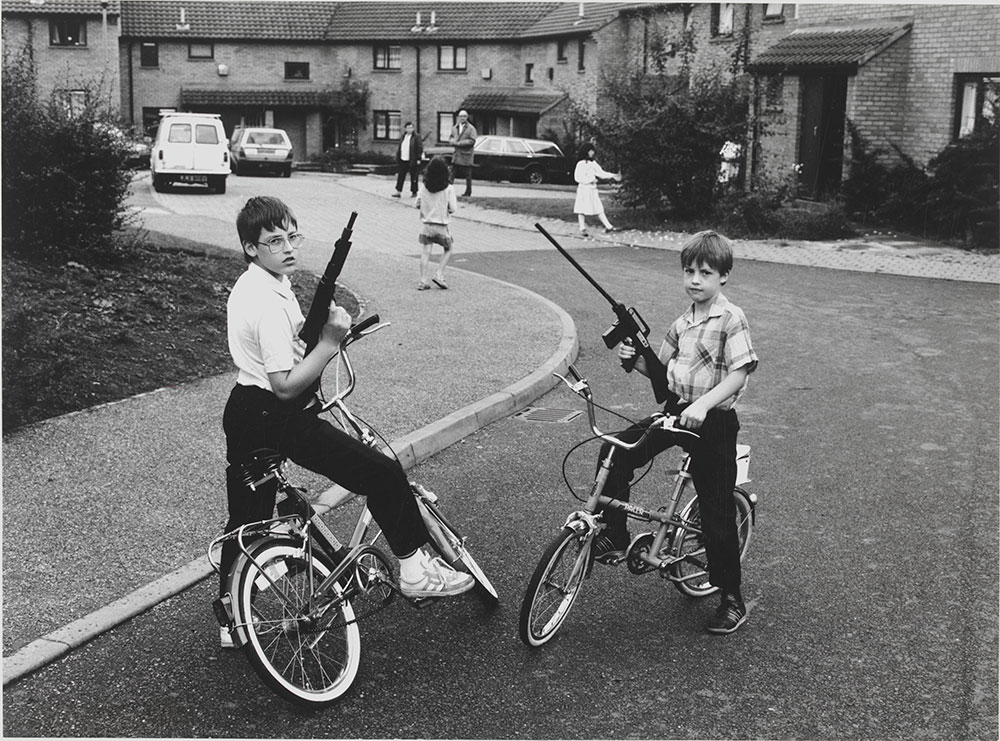

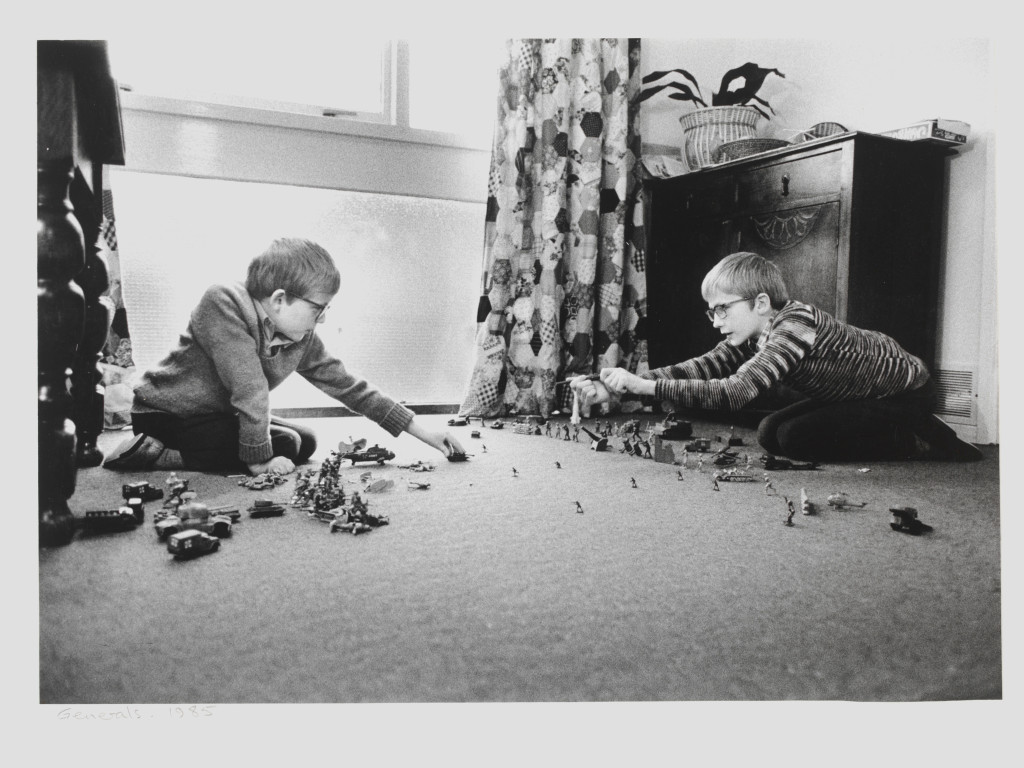

Just opposite are two other photographs, this time by John Heywood (Generals, 1985, and Brothers in Arms, 1987). The first shows what looks like two brothers ‘harmlessly’ playing toy soldiers in a teenage bedroom, in a scene reminiscent of an Enid Blyton novel, whilst the next has the same ‘protagonists’, out on the street, looking directly at the camera, ‘armed’ with highly realistic toy weaponry. The ‘Generals’ have become ‘Brothers in Arms’, transformed from strategic thinkers to child militia.

Another aspect that stood out walking around the show, which is laid out thematically as much as chronologically, was the degree of realism now prevalent and possible in modern ‘wargaming’. The toy soldiers of the 1940’s give way to video games such as ‘Call of Duty’ in the 2000s, with it’s incredibly visceral rendering of simulated conflict scenarios.

The feedback cards displayed on the walls of the gallery, giving visitors the chance to answer the question “I think war games are…?” clearly reflected the age of the respondent. Even if the handwriting wasn’t needed to discern the age gap there was clearly a generational difference between those who thought “War is cool” and those who expressed an air of caution: “Children need to know the difference between what is real and what is fantasy”.

There was a sign of hope amongst this otherwise potentially rather depressing and decidedly unnerving exhibition. When children make their own ‘war toys’ to re-enact conflict, out of twigs or Lego, rather than buying readymade plastic guns, the objects of their imagination manage to assume more sophisticated and positive functions. When left to their own devices it seems kids’ homemade toy guns, put together with whatever is closest to hand, actually reflect a child’s inherent, deep-rooted and humanitarian sensibility. These ‘weapons’, rather than being simply ‘machines for killing’ can teleport, transform and even heal.

Though as inventive as it was interactive, this exhibition (described as ‘battleground to playground’) had to tread a careful path and succeeded for the most part. In an otherwise male-dominated, nostalgic or implicitly violent series of objects, the idea that although conflict may be inevitable, resolution was possible, was necessary and welcome. The show admirably explored a range of ideas including imitation, fantasy, propaganda and patriotism. A display of this kind is both pertinent and valuable. Whilst parents will no doubt enjoy the historical overview and reliving childhood memories, children will certainly engage with the likes of Warhammer and computer game simulations. Judging by the reactions of fellow visitors, parents are keen to raise awareness of the double-edged sword that is ‘playing at war’. It is surely important that the next generation are helped to understand war from all sides. It is quite possible that some of the visitors to this exhibition may be soldiers of the future.

Graham Hooper is an artist, educator and writer living and working in the UK.